Introduction

Cities are civilization’s main stage. More than half the world’s people now live in urban areas, and, like never before, cities are the arenas for addressing the most pressing environmental problems and tackling challenges of sustainable development.

With the Sustainable Development Goals and the Paris Agreement on climate change, national leaders formally recognized cities’ central importance to a coalescing global development agenda. The Habitat III conference held in Quito, Ecuador in October 2016 aimed to define a “new urban agenda” with a broad scope, that includes human settlements of all sizes and integrates social equity considerations into urban and national development planning. Habitat III’s new urban agenda also strives to determine pathways for sustainable urbanization – growing our cities in ways that promote human well-being and enhance environmental health. Urban sustainability’s new prominence and prioritization at the top of the global development agenda represents a moment with critical implications for global environmental health and societal harmony. Researchers, policymakers, and citizens must build a broad base of knowledge on the forces that shape urban lives in order to seize the moment and help shape cities’ development trajectories.

There are many groups and indices that examine urban sustainability, yet these efforts are often sector-specific, regionally-focused, and one-dimensional in scope.1Thomas, R., Hsu, A., & Weinfurter, A. (Forthcoming). Sustainable and Inclusive – Do existing urban sustainability indicators help measure progress towards SDG-11? Standardized metrics and definitions are also lacking, making it difficult to compare urban sustainability initiatives from one city to the next. If we cannot agree on what “urban” and “sustainable” mean, forging a path towards a sustainable urban future is a non-starter. As city governments experiment with sustainability initiatives, their efforts must be measured, assessed, compared with one another, and improved upon, or else we risk missing the results and losing the benefits that these programs can bring to everyone. The global community of urban researchers needs to create a standardized framework of novel urban sustainability metrics in order to realize the potential that cities hold.

Measuring the urban environment in a manner that is both accurate and meaningful to city-dwellers is very challenging. And assessing the relative successes and failures of urban environmental policy is even more difficult. In most urban areas, policies lag behind environmental hazards as cities’ dynamism outpaces governments’ capacity to manage them. Cities are in continuous flux — those in the developing world have expanded at such a breakneck pace in recent decades that their growth has been difficult to manage and their environmental change tough to measure. We observe this phenomenon even in centrally planned cities like Beijing, where rapid industrial and urban growth has led to extreme levels of air pollution. The Chinese government has vowed to clean up the air, pledging blue skies over Beijing within a decade, yet pollution in the country’s second-tier cities is worsening, following a similar trajectory to Beijing’s. Nearly one in five deaths in China can be attributed to foul air.2Thomas, R., Hsu, A., & Weinfurter, A. (Forthcoming). Sustainable and Inclusive – Do existing urban sustainability indicators help measure progress towards SDG-11? Cities all over the world, from Indianapolis to Cairo, face similar challenges: more than 95 percent of people living in urban areas that monitor air pollution are exposed to air quality levels that exceed World Health Organization limits.3Health Effects Institute. (2018). State of Global Air 2018. Special Report. Boston, MA:Health Effects Institute. Available: https://www.stateofglobalair.org/sites/default/ files/soga-2018-report.pdf

Table 1.Targets and Indicators for SDG-11 related to environmental goals evaluated in the UESI.

|

Target |

Indicator |

|

11.1 By 2030, ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums |

11.1.1 Proportion of urban population living in slums, informal settlements or inadequate housing |

|

11.2 By 2030, provide access to safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transport systems for all, improving road safety, notably by expanding public transport, with special attention to the needs of those in vulnerable situations, women, children, persons with disabilities and older persons |

11.2.1 Proportion of population that has convenient access to public transport, by sex, age and persons with disabilities |

|

11.3 By 2030, enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization and capacity for participatory, integrated and sustainable human settlement planning and management in all countries |

11.3.1 Ratio of land consumption rate to population growth rate 11.3.2 Proportion of cities with a direct participation structure of civil society in urban planning and management that operate regularly and democratically |

|

11.7 By 2030, provide universal access to safe, inclusive and accessible, green and public spaces, in particular for women and children, older persons and persons with disabilities |

11.7.1 Average share of the built-up area of cities that is open space for public use for all, by sex, age and persons with disabilities |

Source: UN Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform.4UN Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. SDG- 11. Available: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/ sdg11

Towards Measuring Social Inclusion

The difficulty of defining and assessing the equity considerations of urban sustainability helps explain the shortcomings in existing urban sustainability indicator systems and research. What does equity mean for urban inhabitants who are all confronting severe air pollution, even if that pollution is evenly distributed among residents? Does equity entail redistributing access to environmental goods and amenities from wealthier populations to those with lower incomes? In setting a goal for sustainable and inclusive communities, SDG-11 falls short of defining what is meant by these complex, context-specific terms of inclusivity and community.

We therefore define social inclusion as the process of ensuring all members of society have both representation and agency in shaping the decisions that determine their social, political, economic, and cultural lives. Social inclusion can enhance and may reflect the strength of social connectedness, the degree to which individuals and communities are working together to overcome isolation and to foster belonging and solidarity. This definition draws on discussions of inclusive and sustainable development,5Gupta, J., & Vegelin, C. (2016). Sustainable development goals and inclusive development. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 16(3), 433-448.6Dempsey, N., Bramley, G., Power, S. and Brown, C. (2011), The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustainable Development, 19: 289–300. doi:10.1002/sd.417 http:// onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/sd.417/full. distributive justice, 7Schlosberg, D. (2007). Defining environmental justice: Theories, movements, and nature. Oxford: Oxford University Press.8Dempsey, N., Bramley, G., Power, S. and Brown, C. (2011), The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustainable Development, 19: 289–300. doi:10.1002/sd.417 http:// onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/sd.417/full9Fraser, N. (2001). Recognition without ethics? Theory, culture & society, 18(2-3), 21-42.social exclusion10Levitas, R., Pantazis, C., Fahmy, E., Gordon, D., Lloyd, E., & Patsios, D. (2007). The multi-dimensional analysis of social exclusion.11Eurostat Taskforce on Social Exclusion and Poverty Statistics. (1998). Recommendations on social exclusion and poverty statistics (Luxembourg, Eurostat).12Hayes, A. Gray, M. & Edwards, B. (2008). Social Inclusion: Origins, concepts and key themes. Australia. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Social Inclusion Unit; Australian Institute of Family Studies (AIFS)., well-being, 13Gupta, J., Pouw, N., & Ros-Tonen, M. (2015). Towards an elaborated theory of inclusive development. European Journal of Development Research, 27, 541–559.and social cohesion.14Acket, S., Borsenberger, M., Dickes, D., & Sarracino, F. (2011). Measuring and validating social cohesion: A bottom-up approach. In CEPS-INSTEAD Working Paper.15Bernard, P. (1999). Social cohesion: A critique. Canadian Policy Research Networks.16Chan, J., To, H. P., & Chan, E. (2006). Reconsidering social cohesion: Developing a definition and analytical framework for empirical research. Social indicators research, 75(2), 273-302.

In this context, social inclusion means more than having a seat at the table – it encompasses facilitating inclusion by removing obstacles to participation17United Nations. (2016). Report on the World Social Situation 2016. Leaving no one behind: the imperative of inclusive development. Retrieved from: http://www. un.org/esa/socdev/rwss/2016/chapter1.pdf.18Fainstein, S. S. (2010). The Just City. Cornell University Press.and ensuring that representation in these decision- making forums has real weight. There are clear links between social inclusion and the urban environment. Mounting evidence shows that environmental health is increasingly viewed as a commodity for urban citizens who can afford it, a paradigm that leads to environmental injustices and exclusion. 19Questel, N. (2009). Political Ecologies of Gentrification. Urban Geography, 30(7), 694–725.Studies in political ecology, environmental planning, and gentrification have shown that social exclusion undermines environmental goals and erodes a city’s ability to provide for its citizens, combat climate change, and compete in the global economy. 20Kneebone, E, and Alan, B. (2013). Confronting Suburban Poverty in America. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press.21Shi, L., Chu, E., Anguelovski, I., Aylett, A., Debats, J., Goh, K., … VanDeveer, S. D. (2016). Roadmap towards Justice in Urban Climate Adaptation Research. Nature Climate Change, 6(2), 131–137.Cities are inherently social places and the success of urban governance needs to be gauged according to the needs of city residents.

A New Approach to Understanding Social Inclusion and the Urban Environment

To better understand the links between the urban environment and social inclusion, it is our aim to institute a data-driven approach. Robust metrics allow cities to identify urban sustainability priorities, set goals, and benchmark their progress over time. Hurdles to accessing and interpreting data can often reduce citizens’ ability to participate in discussions around environmental management. Information is a means of providing people with agency and of removing obstacles to engaging in social, political, economic, and cultural discussions and decision-making. Social inclusion and social connectedness occur – and can be measured – at various and overlapping scales, from households to neighborhoods to entire societies. Monitoring efforts may observe and collect both qualitative and quantitative data as they seek to: (1) create a complete assessment of a neighborhood or city’s demographics (e.g., ensure marginalized populations or neighborhoods are included in the definition of a city’s population); (2) track how representation and agency vary according to these demographics; (3) measure the ways social, economic, and environmental benefits and burdens are distributed across these demographics; and (4) assess levels of resilience and community-driven actions across these demographics.

The Urban Environment and Social Inclusion Index (UESI) is a tool and research project that helps city leaders track progress towards Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Goal 11 – to make cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable. The UESI provides a new, spatially-explicit approach to evaluate how different neighborhoods within cities vary in terms of environmental performance and social inclusion. By making neighborhood-level environmental and socio-economic data easily accessible, we hope to increase opportunities for social inclusion by connecting urban residents with information about their environments.

The Index seeks to empower urban residents, providing tools that enable them to track their neighborhood’s access to environmental benefits and burdens relative to other city districts. An open snapshot of a city’s environmental performance provides a shared starting point and frame of reference for residents and policymakers as they identify environmental management priorities and develop management strategies to meet these goals. The world’s cities are diverse, like its people, and this variety – in geography, development stage, and governance, among other issues – creates challenging complexity for standardization efforts. A measure that reports a city’s impact on the marine environment, for instance, would be less applicable to Denver than it would be to New York City. And sustainability initiatives in rapidly expanding cities may be very different from those in urban areas with only modest growth. Yet even disparate cities are able to teach and learn lessons from one another. Lagos, Nigeria could learn from Singapore’s water recycling initiatives; Houston, Texas could learn from Bogota’s bus-rapid transit system. In these interactions, standardized sustainability metrics would give nations and cities a common language to communicate their initiatives’ successes and failures.

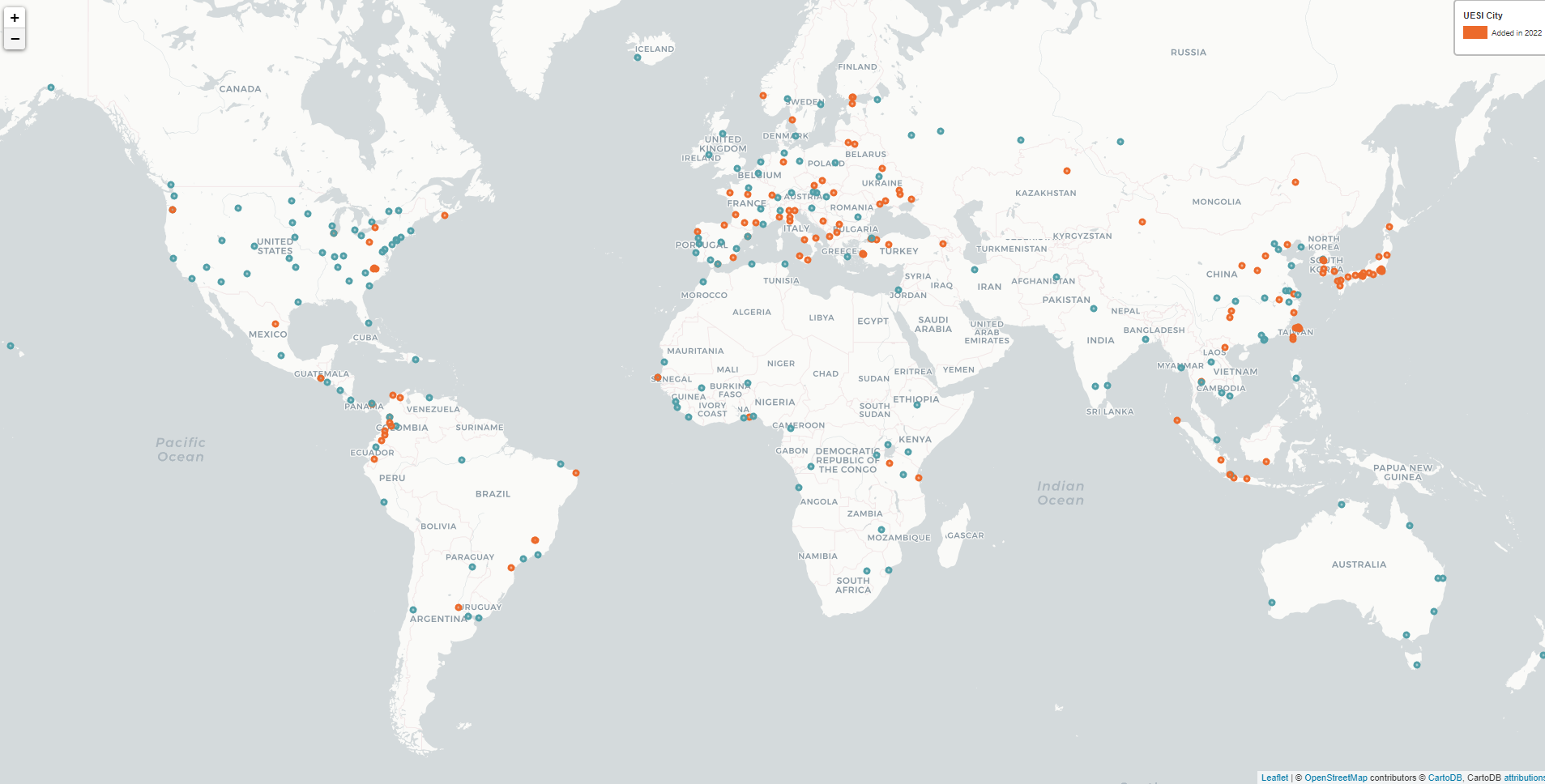

A pilot version of the UESI, launched in December 2018, included over 30 cities across a range of geographies and levels of economic development (Figure 1). In 2019, the Index was expanded to include over 160 cities, with at least one city from each continent, excluding Antarctica, and a range of large and small, capital and non-capital cities. Data availability was the strongest determinant for whether a city was included; the lack of neighborhood-level income and population data and spatial data for city districts were typically the greatest obstacles to including cities in the UESI.

The UESI now includes nearly 300 cities, spanning six continents and 95 countries, representing about 10 percent of the global population and about 18 percent of the 4.4 billion people that live in cities worldwide, as estimated by the World Bank.

A majority of UESI cities are located in Europe and Asia – about 30% and 28% of all cities in the Index, respectively – while 17% of cities are in North America, around 10% are each in Africa, Latin America, and Caribbean, and 3% are in Oceania. These numbers reflect a growth from the first 32 pilot cities in the UESI, which was launched in 2018. Since then, more than 250 cities have been added, with 118 cities added in 2023, including 41 from Europe, 54 from Asia, and 21 from Latin America and Caribbean. Many of these cities have recently made climate mitigation pledges, such as setting a target for net-zero emissions, which is why we’ve added them to the Index.

Figure 1. Map of cities included in the UESI.

Box 2. Characteristics of Neighborhoods within UESI Cities

One of the most crucial questions in assessing a city’s performance is the scale of the analysis. There are four key scales when examining urban areas: parcel (data at the census or city block level), neighborhood (groups of parcels), regional (which can defined according to political, economic, or geographic boundaries), and macro systems (defined according to the national, ecosystem, and global factors shaping urban areas). Table 2 below provides examples of these scales.

Although each city defines what a “neighborhood” is differently, according to their own standards, the UESI adopts the neighborhood as the primary unit of analysis for several reasons. First, we aim to provide a detailed evaluation of environmental performance and social inclusion in a spatially-explicit way that allows citizens and urban managers to understand how these phenomena vary across a city and affect different populations. Adopting a scale coarser than the neighborhood level (i.e., regional or macro-system) would not provide the resolution to allow for an investigation of this variation. Second, although some cities’ analysis may warrant a scale even finer than the neighborhood scale, not every city in our sample has data at that level (e.g., at the census or block level). We therefore had to strike a balance between granularity and data availability to allow for comparison across cities.

Table 2. Examples of various urban scales and examples of data for each particular scale.

|

Scale |

Example data |

|

Parcel-level |

Data at a fine scale, e.g., at the level of census tracts or city block(s). In addition to census- level data (such as information about a parcel’s demographics), data at this scale can include detailed data such as the locations of businesses, geolocated tweets, the location of intersections, and air quality monitors. |

|

Neighborhood |

Data aggregated or available at resolutions of 1-50 square km. Examples of neighborhood-level data include the average income of urban districts, urban tree canopy at 30m resolution, and population density. |

|

Regional |

Regional data related to the urban system, which could be defined by political boundaries, regional economic systems, contiguously built-up areas, and natural areas such as watersheds and commute sheds. This data can focus on the urban agglomeration by itself, or include surrounding rural areas. |

|

Macro system |

Broader circumstances of urban areas may put pressure on the built environment. |

Source: Adapted from Sipus, 201722Sipus, M. (2017, February 12). Humanitarian Space [Blog]. Retrieved April 5, 2017, from http://www.thehumanitarianspace.com/; Buchanan, 2001; 23Buchanan, R. (2001). Design research and the new learning. Design Issues, 17(4), 3–23.and Golsby-Smith, 1996.24 Golsby-Smith, T. (1996). Fourth Order Design: A Practical Perspective. Design Issues, 12(1), 5–25.)

Organization of this Report

The report contains an overview of how each UESI indicator was calculated and the rationale behind its inclusion. Further information about each indicator’s data sources, transformations, and other details are accessible through the Methods section, each Issue Profile and in forthcoming academic literature. All UESI data and results are available for free download and use under a Creative Commons license.

The UESI report is organized as follows:

- The Key Findings section provides an overview of some of the main findings for the nearly 300 160+ cities included in the UESI.

- A brief Methods chapter provides a general overview of how we determined the UESI framework and calculate the proximity-to-target indicators, although more methodological details are provided in each chapter.

- A chapter on Equity and Social Inclusion details our new approach to evaluating how cities are meeting the challenge of achieving environmental performance in an equitable and inclusive way.

- Five issue profiles explain the methods used to calculate the UESI’s urban environment and social inclusion indicators. These sections frame each environmental problem included in the UESI, and examine the complexities involved in developing spatially-explicit measures of urban environmental performance and social inclusion at the neighborhood scale.

- A Results for Pilot Cities section provides an overview of how 32 cities included in the pilot version of the UESI compare on the environmental indicators selected, and explores overall trends in environmental performance and social inclusion.

- A Conclusions section describes areas of uncertainty and points to future areas of research.