Image by fabio/Unsplash.

The following whitepaper was written by Dr. Angel Hsu, Willie Khoo, Amy Weinfurter, Brendan Graetz, Barnabé Monnot, Ying Tong Lai, Qing Ze Hum, and Koh Wei Jie, a group of climate experts and computer scientists who came together at the Open Climate Collabathon. The proposed solution, PreciDatos, was presented at a COP25 side event in Madrid titled ‘Radical Collaboration For Climate Change: Digital Solutions for Tracking Progress,’ where it won the Most Innovative Award.

Table of Contents

Abstract

Cities, states and regions, companies, and investors play a critical role in meeting the urgent need to reduce emissions and transition to a decarbonized society and economy. They are directly taking climate actions by setting their own emissions reduction targets, establishing their own renewable energy targets, and committing to ambitious goals like striving for net-zero emissions by mid-century. Data is crucial for tracking these voluntary commitments by these actors. It can help us understand what actors’ climate commitments are and whether they are following through, thereby providing accountability and preventing greenwashing. However, tracking climate data remains challenging–it is costly, inefficient, and inconsistent. Distributed ledger technology could provide the infrastructure necessary to tackle these challenges. We propose a blockchain-based data reporting system that economically incentivizes actors to disclose accurate data using zero-knowledge proofs. The system may be further extended to include homomorphic encryption and Natural Language Processing (NLP) modules for greater privacy and more efficient data preprocessing.

Introduction

Policymakers’ slow response to climate change has made the next decade a make-or-break moment for avoiding the most catastrophic impacts of climate change. The 2015 Paris Agreement sets a goal of keeping global temperature rise “well below” 2°C compared to preindustrial levels, with further efforts to prevent global temperatures from rising past 1.5°C. Yet the gap between what countries have pledged to do to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and what they need to do to meet the Paris Agreement goals has grown four-fold since 2010 (Höhne et al., 2020).

Cities, states and regions, companies, and investors play a critical role in meeting the urgent need to reduce emissions and transition to a decarbonized society and economy. They are directly taking climate actions by setting their own emissions reduction targets, establishing their own renewable energy targets, and committing to ambitious goals like striving for net-zero emissions by mid-century. As of February 2020, the Global Climate Action Portal, which collects climate action commitments that these actors have made across the world’s largest reporting platforms, included 17,284 actors making over 25,000 commitments (UNFCCC, 2020), a dramatic rise from the 5,000 actors captured by the platform in 2015 (Hsu et al., 2015). If fully implemented, existing city, region, and company commitments made in ten of the world’s largest economies could narrow the emissions gap by 1.2-2.0 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide, an amount equivalent to roughly 4% of current global emissions (NewClimate Institute et al., 2019).

Data is crucial for tracking these voluntary commitments by cities and companies. It can help us understand what actors’ climate commitments are and whether they are following through, thereby providing accountability and preventing greenwashing. Understanding the full scope of participation in climate action also ensures that the needs and perspectives of different climate actors are reflected in global policy agendas. For instance, research suggests that existing climate action reporting platforms do not fully capture climate action underway in emerging and developing economies (Hsu et al., 2015; Hsu et al., 2018; ClimateSouth, 2018). Data can be one way of documenting climate action and ensuring these stakeholders have a voice in global agenda-setting as well as access to financial and technical resources through knowledge and best-practice sharing networks, such as the C40 Cities for Climate Leadership (C40 Cities) or CDP (formerly Carbon Disclosure Project). Further, such information can facilitate efforts for cities and companies to identify peers and potential partners, supporting efforts to create coalitions focused around a shared goal, or to exchange approaches and strategies with peer actors. Finally, data can allow national governments to create policy environments that encourage and support climate action from cities and the private sector. Countries can also leverage information about voluntary local, regional and corporate action to increase national ambition, by scaling up successful strategies, integrating them into national policies, and replicating them in other locations.

Challenges of Climate Data Tracking

Tracking climate data remains challenging, for the reasons outlined below:

Existing methods of data collection and analysis are time-consuming, inconsistent, inefficient, and costly. The process of reporting progress towards mitigation, adaptation, or finance targets can be a time-consuming and challenging process. CDP estimates that completing its annual Supply Chain Questionnaire takes a corporation over 100 hours (Andersen, 2015). Many mitigation commitments, for instance, rely on emissions inventories, which rely on an actor’s activity data (e.g., the fuel combustion in stationary sources) multiplied by emissions factors, the greenhouse gas emissions produced for each fuel type or by a specific activity (Hsu et al., In Submission). Gathering and calculating all this data requires significant expertise, capacity, and time; some evidence suggests that the daunting requirements needed to conduct a greenhouse gas emissions inventory can prevent actors from implementing a climate action strategy (Markolf et al., 2017). Actors also often participate in several networks with different reporting requirements, leading to reporting fatigue or failure to report altogether, as a result of limited resources to develop timely and regular GHG inventory reports.

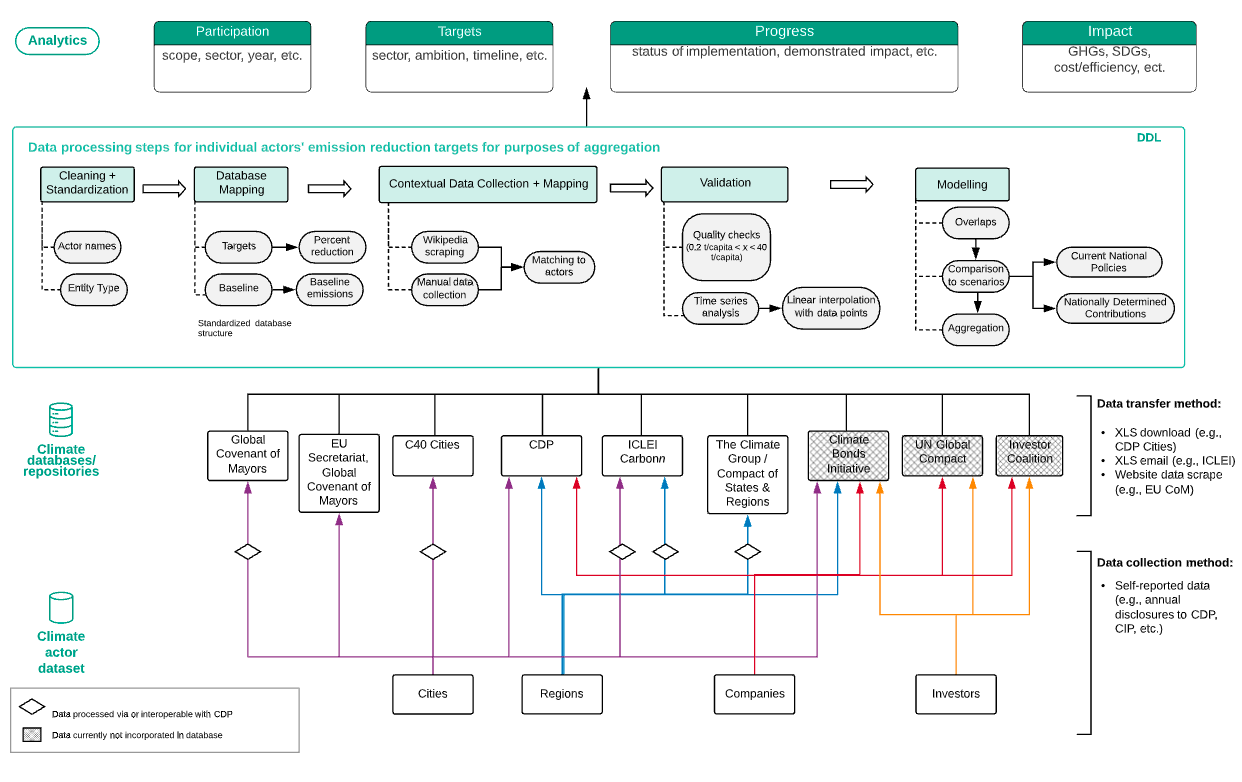

Moreover, the data that is collected often varies significantly both within and across different reporting platforms (see Figure 1). Actors report varying target years, base years, and baselines for evaluating impact (Hsu et al., 2019), making it challenging for analysts to compare or aggregate the impact of climate action commitments. They also often focus on different kinds of data. For instance, there is a great deal of variation across commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions: some commitments cover direct or Scope 1 emissions, which measure direct emissions from sources owned or operated by the actor, such as a furnace or boiler that directly combusts fossil fuels; while others cover indirect emissions, which reflect emissions from purchased electricity, heat, or steam (Scope 2), or emissions embedded upstream or downstream in an actor’s supply chain (Scope 3) (Fong et al., 2015). Many sectors or categories are often excluded from emissions inventories, but form a large part of actors’ emissions footprints (Hsu et al., In Submission). For instance, many cities and companies exclude Scope 3 emissions from their inventories, despite the fact that they often form a significant share of these actors’ total emissions (Ramaswami et al., 2008; PBPS, 2015; Kennedy et al., 2009). The role that forests and agriculture play as carbon sinks or sources are also challenging to quantify (Ramankutty et al., 2006), and often missing from inventories as a result.

Tracking progress towards climate action commitments remains challenging, due to gaps and inconsistencies in reporting. Ideally, data tracking climate commitments and progress towards them would be available across multiple years. In practice, although some data reporting platforms and networks ask participants to track progress towards their commitments, only a small fraction of participating actors do so (Hsu et al., 2018; Hsu et al., 2019). Even when actors share data of their progress, such as the percentage of emissions reductions or renewable energy achieved, it can be inconsistent over different years, making it difficult to track performance over time. Additionally, vital contextual information, such as an actor’s overall emissions or energy mix, is often missing, making the assessment of impact difficult (Hsu et al., 2019).

Incentives are not aligned across reporting organizations. Many actors may participate in several different platforms in order to gain access to different benefits and networks (see Figure 1). Others may not be able to justify the allocation of scarce resources to join these efforts based on existing — and often intangible — incentives. Motivations can also vary across different actors — companies in the consumer goods sector, for instance, may be highly attuned to their reputation among consumers, while others sectors, such as the chemicals industry, may be more insulated from public opinion, and more responsive to factors such as investor pressure (Rust, 2019).

Some emissions data are considered sensitive and could reveal proprietary information. Greenhouse gas emissions data, which forms a key part of climate reporting, can be proprietary or confidential. In some governance contexts, emissions data may be politically sensitive. Many companies hesitate to report on or share sustainability innovations, to avoid tipping off potential competitors, out of a concern that customers equate sustainability with cost increases, or out of a fear of inviting scrutiny into other areas of the company’s operations (Coburn, 2019). If a company reports an intensity-based metric alongside baseline or inventory greenhouse gas information, for example, it could be possible for competitors to determine the company’s production costs, or other data that could harm the reporting business’s competitive advantages. CDP, the primary reporting platform for businesses, gives companies the option to report on their climate action commitments privately rather than publicly, a strategy that may help address these concerns.

Figure 1. A diagram showing the existing workflow of data collection, processing, and analysis for climate commitments made by cities, regions, companies, and investors.

Opportunities for Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT)

The concept of blockchain as a distributed ledger technology (DLT) first appeared with the release of Bitcoin’s whitepaper in 2008 (Nakamoto, 2008). While early focus was directed towards the wastefulness of its energy consumption, the UNFCCC (2017) has since established the potential of blockchain technology to address climate change. Blockchains and distributed ledgers could provide the infrastructure necessary to uniquely and transparently record climate data, including carbon emissions, green financial instrument trades, and climate action commitments. The integration of these disparate, possibly private, data sources (emissions, trades, and commitments) in a single, cryptographically-verified ledger forms the basis of ‘system of systems’ approaches, such as the Open Climate platform proposed by Wainstein et al. (2019).

Blockchains supporting cryptocurrencies, in particular Ethereum, have become experimental grounds for various green projects, such as automated carbon emissions recording and offsetting (Chen, 2018). The use of cryptocurrencies to incentivize green behavior is a design pattern noted by Herweijer et al. (2018) and has been implemented by projects such as Power Ledger and Swytchx. These platforms allow companies to create different types of digital green assets, such as energy consumption and production records, CO2e measures of carbon offset or liability, and Renewable Energy Credits, which may be traded or retired at a later point (Power Ledger, 2020; Swytchx, 2019). Cryptocurrencies thus allow for more than a simple record of financial transactions on blockchains, creating instead an economic space where user contributions are rewarded with a token native to the platform. Such tokens are often traded in exchanges or allow their bearers to pay for services, giving rise to autonomous circular economies.

The Blockchain for Climate Action Tracking (B-CAT) Framework

The increasing recognition of blockchain’s potential to tackle climate change has led to the development of the Blockchain for Climate Action Tracking (B-CAT) framework by a group of academics, blockchain experts, and entrepreneurs. Supported by the National Science Foundation’s Science of Science Policy and Innovation Program, B-CAT identifies the key actors in the climate action ecosystem and maps out the blockchain design components necessary for incentivizing these actors to fill existing data and knowledge gaps (Data-Driven EnviroLab, 2019). Building on that earlier research, this whitepaper proposes a specific technological solution for use within the B-CAT framework, and suggests directions for prototype-building so as to expedite the development and adoption of blockchain as well as other emerging technologies for stronger climate action beyond 2020.

Proposed System

Our proposed system, PreciDatos, is a blockchain-based data reporting system that economically incentivizes actors to disclose accurate climate data. Here we define ‘accurate data’ as data that is valid (i.e., complete and in a structured format) and truthful (i.e., not corrupted by the reporter). Utilizing zero-knowledge proofs and a staking mechanism, the system ensures validity and truthfulness–and hence accuracy–of data, providing an auditable and verified dataset for increased transparency. The system may be further extended to include homomorphic encryption and Natural Language Processing (NLP) modules for greater privacy and more efficient data preprocessing.

PreciDatos is a technological component of B-CAT and was conceived during the Open Climate Collabathon 2019. It was later presented at a COP25 side event in Madrid titled ‘Radical Collaboration For Climate Change: Digital Solutions for Tracking Progress,’ where it won the Most Innovative Award (Data-Driven EnviroLab, 2020).

System Architecture

Types of actors

All actors wishing to participate in the PreciDatos system must come together in a blockchain consortium. A blockchain consortium is a permissioned blockchain network comprising and maintained by multiple organization-level actors. In the consortium, we consider the following three actor types:

- Honest actors with accurate data: These actors have meaningful climate action goals, and the financial and technical resources to measure and report progress towards them.

- Honest actors with inaccurate data: Many actors set and aim to track progress towards their targets, but face obstacles in the form of limited staff capacity, changes in political climates, or the cost of implementing and recording commitments. Data reported by these actors can be very difficult and time-intensive to clean and analyze, and may not contain sufficient information to be included in climate action analyses.

- Greenwashing actors: Some actors may intentionally disclose inaccurate data (e.g., the Volkswagen emissions reporting scandal (Hotten, 2015)) or make goals that do not represent a meaningful share of their overall emissions footprint. For instance, an investor may make a commitment to reduce the emissions from buildings that house its day-to-day operations, but fail to address the much larger share of emissions embedded in its investment portfolio. A large oil and gas company may make an investment in clean energy, without sharing the context that this constitutes just a small fraction of its overall investments, which still disproportionately fund fossil fuels.

Staking

There is no obvious reward for actors to implement robust data reporting practices, nor is there a penalty for poor reporting. Moreover, actors benefit in reputation from the act of reporting itself, regardless of the quality. We propose that actors stake some funds in order to commit to the quality of their data. Staking in this case refers to the process of locking funds on a blockchain to participate in the system. The stake can come in the form of cryptocurrency, or fiat money with an on-chain record of that commitment. The mechanism should guard against penalizing too harshly companies who do not fulfill their commitments, as this would incentivize lower commitments altogether.

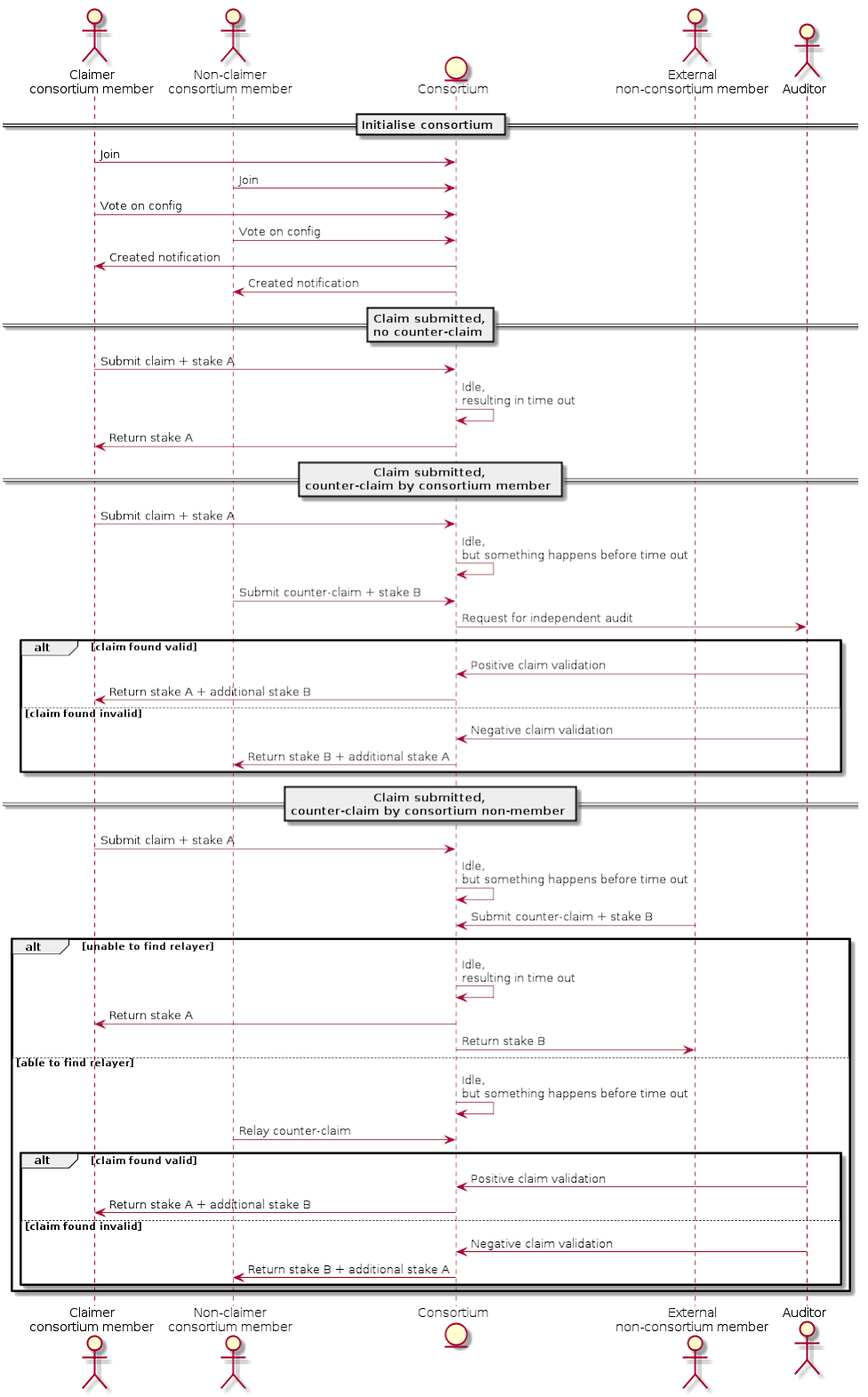

For honest actors with accurate data: The staked amount is returned in full, with the possibility of including a reward, depending on available funds (see Discussion). For honest actors with inaccurate data: The staked amount covers additional data processing steps should they be required, paying for bounties or open-sourcing the work. For greenwashing actors: The staked amount is used to produce an investigation into the accuracy of the data when counterclaiming takes place. These outcomes are summarized in Figure 2, and described in detail subsequently.

Figure 2. Illustration of the sequence of actions between various actors in the PreciDatos system.

Reporting

An actor submits a report by committing to the following pieces:

- Data resources (any format)

- Report metadata (type of report, level of detail)

- Stake

- Committee members

Ideally, the stake should broadly correspond to the amount and granularity of the data: larger reports take longer to process or find flaws, while in the worst case of fraudulent data reports investigations are more costly. The actor commits to the report by digitally signing it on the blockchain.

Standardized Data Format

We define the ideal standard data format for each report type. Note that companies may decide not to follow the standard data format, using their staked funds or potential reward to pay for standardization. The data schema should have a sub-schema within it that can differ for various use cases. For example, a plastics clean-up report would have a different sub-schema from a solar power generation report. The approximate structure (pseudocode style) of the schema and its fields would look like this:

- Date

- Digital signature

- Staked amount

- Report

- Sub-schema

- List of claims

- Would be most simple if only considering emission reduction commitments as opposed to other commitment types (i.e., renewable energy installation, energy efficiency) but this system could start with emission reductions and then be scaled to other commitment types.

- Emission reduction commitment (percent reduction, base year, target year, boundary/scope (e.g., location of emission reductions, specific sectors that are included/not included)

- Progress on emission reduction commitment (inventory year emissions disaggregated by Scope (Scope 1, 2, 3) (must be at least 1 year later than the base year inventory emissions)

- Proofs of claims

- Electricity bills, renewable electricity generation, employee commuting records, disclosure reports by climate databases (e.g. CDP), inventory audits, data collected from Internet-of-Things (IoT) devices, etc.

- List of claims

- Sub-schema

The report and invoice data may make use of homomorphic encryption to allow for privacy, while still being able to compute aggregate data (see Discussion).

Challenging

Validation Challenge

The data may be challenged on the grounds that it is not well-formed, in the case of an honest actor with inaccurate data. All parties participating in this consortium, including both the payers and payees, need to validate a submission. This includes the following:

- Digital signature verification

- The signature has been signed by the submitter

- The signature is valid for the data submitted

- Schema

- That the format of the submission is valid according to the schema

- That the format of select parts of the submission is valid for the specific sub-schema for the use case used by members of this consortium

- Application of business rules

- Various parts of the submitted data need to be verified according to business rules specific to the use case used by this consortium

- For example, the calculations used to work out how much is payable per unit of work used

- Various parts of the submitted data need to tally with the invoiced amount

- Any automatic verification of proofs of claims

- For example, comparing to known sources of data such as weather reports, satellite data, and any custom sensors that have been installed

- Various parts of the submitted data need to be verified according to business rules specific to the use case used by this consortium

Any party participating in the consortium, upon completing validation, is expected to, in most cases, discover that a submission is valid. However, in some cases, it may discover that the submission is in fact invalid. In this latter scenario, that party may decide to issue a challenge.

Signalling

A party that has performed validation, found a submission to be invalid, and decided to challenge it, will signal its challenge to all members of the consortium. The intended effect of signalling this challenge is to state that the submission cannot be accepted by the consortium, and thus to trigger an investigation into the claims. The approximate structure (pseudo code style) of the schema and its fields of the signal should look as follows:

- Date

- Zero-knowledge proof of membership

- Staked amount

- Report

- Sub-schema

- Proofs of contradictions of claims

- Sub-schema

In order to avoid unnecessary or frivolous investigations — since these are assumed to require significant time or resource investments — a staking mechanism is introduced. This is where the party submitting the challenge also deposits an amount as part of the challenge signal. This deposit amount from the challenging party, along with the amount that is owed to the submitting party, is locked up in an escrow mechanism.

As members of the consortium do not necessarily want each other to know who has issued the challenge signals, the challenge proof will contain a zero-knowledge proof that verifies that the submitter of the challenge is a member of the set of parties in the consortium, without the need to reveal their own identity.

Counterclaiming Challenge

While the immutability of records stored in blockchains provides guarantees against falsification, it does not protect against an initial falsification at the time of input. Data may be falsified by the reporting actors, and challenging may be individually damaging to the counterclaimer. The mechanism offers economic incentives and an anonymous yet verifiable procedure for an informed counterclaimer to act. A counterclaimer is different from a validation-challenger (above) in the following ways: They are an individual, rather than an organisation, and they are able to provide proofs of contradictory evidence.

When a submission contains a proof for a particular claim, and the counterclaimer has evidence that this proof is fraudulent in some way, that person may decide to signal a challenge containing details of said proofs, using a procedure similar to the one used by organisations. Just like an organisation challenge, the counterclaimer challenge will contain a deposit amount, and staking mechanisms remain the same.

As a counterclaimer is likely to be an individual within an organisation (that is itself a member of the consortium), and quite likely to be an employee or a contractor, they have a strong incentive not to counterclaim out of fear of retribution, such as the cancellation of employment or contract. In order to protect against this, the signal submitted by the counterclaimer will contain a zero-knowledge proof that verifies that the counterclaimer is a member associated with a member of the consortium, without the need to reveal their own identity.

A limitation of this system is the perverse incentive for organisations to minimise the count of individuals who are designated as members, so as to increase the likelihood of identifying the counterclaimer. For example, an organization could decide to have only one member in its climate data reporting department, thereby thwarting any anonymity of counterclaiming. Perhaps, even more cynically, the organization could influence organisations to select certain profiles of individuals to be designated as members of the organisation.

To address this limitation, we propose that an alternative path could be taken in the implementation of the counterclaiming process. Firstly, we continue to allow people who are able to prove that they are a member of the organisations that are members of the consortium to counterclaim, without revealing their identity. Additionally, we allow a signal by any person — without the need to prove their membership — for consideration by the members of the consortium. However, unlike a signal where there is proof of membership, in this case, the signal must be “relayed” by members of the consortium in order to be able to trigger an investigation. Should an insufficient number of consortium members do this, this particular signal is effectively ignored. On the other hand, if the public is educated about the counterclaiming mechanism, organisations with a high number of potential counterclaimers but relatively low number of reports are likely to be viewed in a good light. Such a reputation-based system would encourage organisations to have as many of their members be registered in the system and also to report data truthfully.

Quorum

Each consortium will pre-agree upon the quorum required to trigger an investigation. It may also pre-agree upon different quora required for different levels or tiers of investigation. In this scenario, it may even pre-agree upon different minimum required deposits for each tier of investigation. Further to this, the consortium may also agree upon different quora requirements for organisation-submitted challenges and counterclaimer-submitted challenge. These pre-agreed quora values start off as part of the initial consortium configuration, and may change beyond the initial configuration upon consensus by parties to the consortium.

Proofs

All submissions should contain proofs. Both identity and proof data are revealed here. All challenge signals should also contain proofs. Identity is not revealed for challenges, but rather in the form of zero-knowledge proofs that may optionally show membership of a set. Where membership of the set is not shown, any member of the consortium may relay the challenge signal, and include their proof of membership of the set. The proof data is revealed. Both submissions and challenges, in addition to data, also contain a staked amount. This stake is key to proper economic incentivization.

Proofs are key in minimizing fraudulent data, and thus are central in any implementation of this system. As proofs are costly to acquire, they also need to be adequately compensated, and this comes in the form of incentives for honest (correct) submissions, and disincentives for dishonest (incorrect) submissions.

Investigation

When a challenge results in an investigation, that investigation should be carried out by an independent auditor using real-world (non-computer) techniques. The auditor, or the auditor selection process, should be pre-agreed upon by the parties in the consortium. Ideally, these auditors should be randomly selected from a pool of qualified auditors. When the investigation is completed, the result of that investigation is input back into the computer system. This input’s primary purpose is to release the amounts locked up in escrow pertaining to the investigation. The input would apportion the fraction of the amount to the challenging party and the submitting party.

If the submission (by the organization) was deemed to be fraudulent, the challengers get all of the deposited amount. If the submission was deemed to be correct, the submitter gets all, or some, of the deposited amount. As with other escrow systems, a portion of the deposited amount will go to neither the submitter nor the challenger, and this is used to pay for the investigation. The exact fraction of the deposit which will be paid out, and to whom, can be programmatically configured to reflect an optimal game-theoretic equilibrium.

User Flows

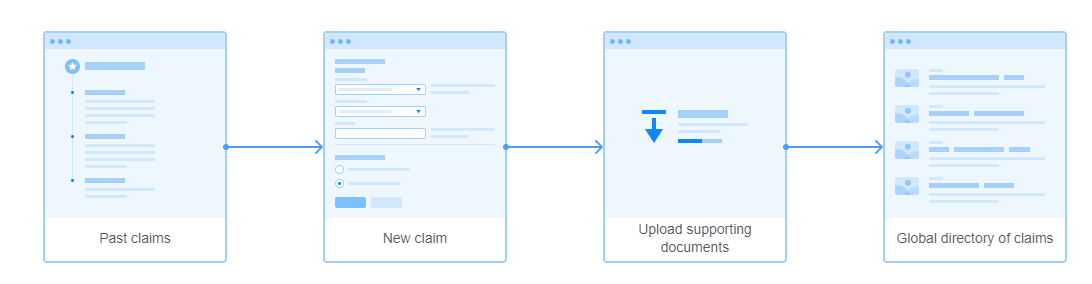

We provide a demonstration of what a typical user flow might look like from the perspective of the potential actors of the platform, namely organizations and individual users.

Organization’s perspective:

Figure 3. User flow from an organization’s perspective. The organization has its own page and is able to create and stake its emissions claims.

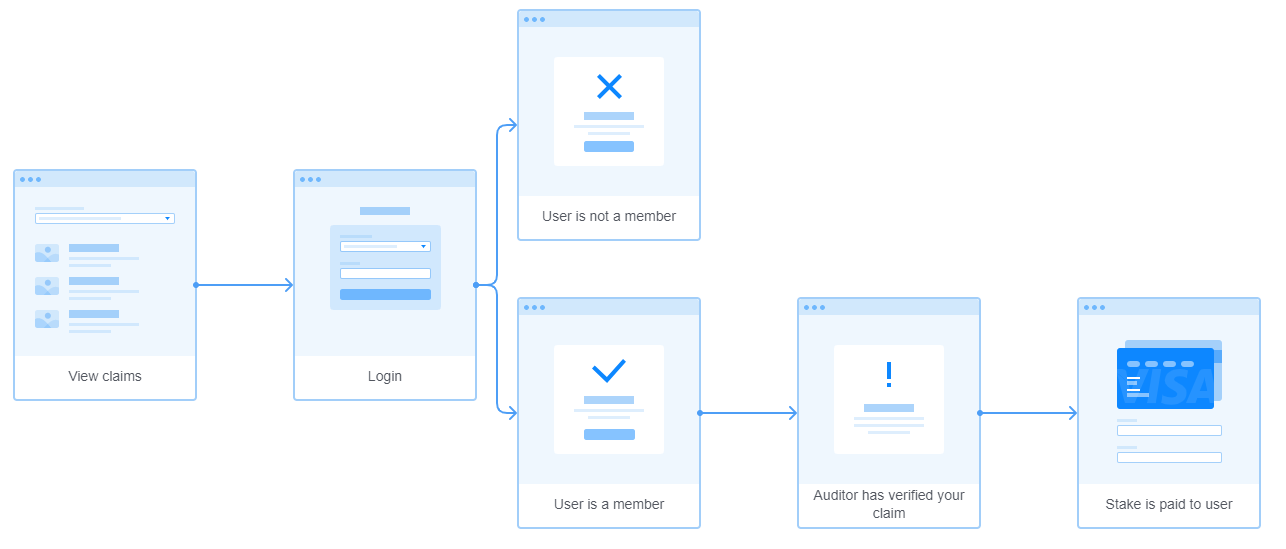

User’s perspective:

Figure 4. User flow from an individual user’s perspective. The user can view existing claims but must be a verified member of the organization in order to successfully challenge them.

Proof of Concept: Solar Energy Production

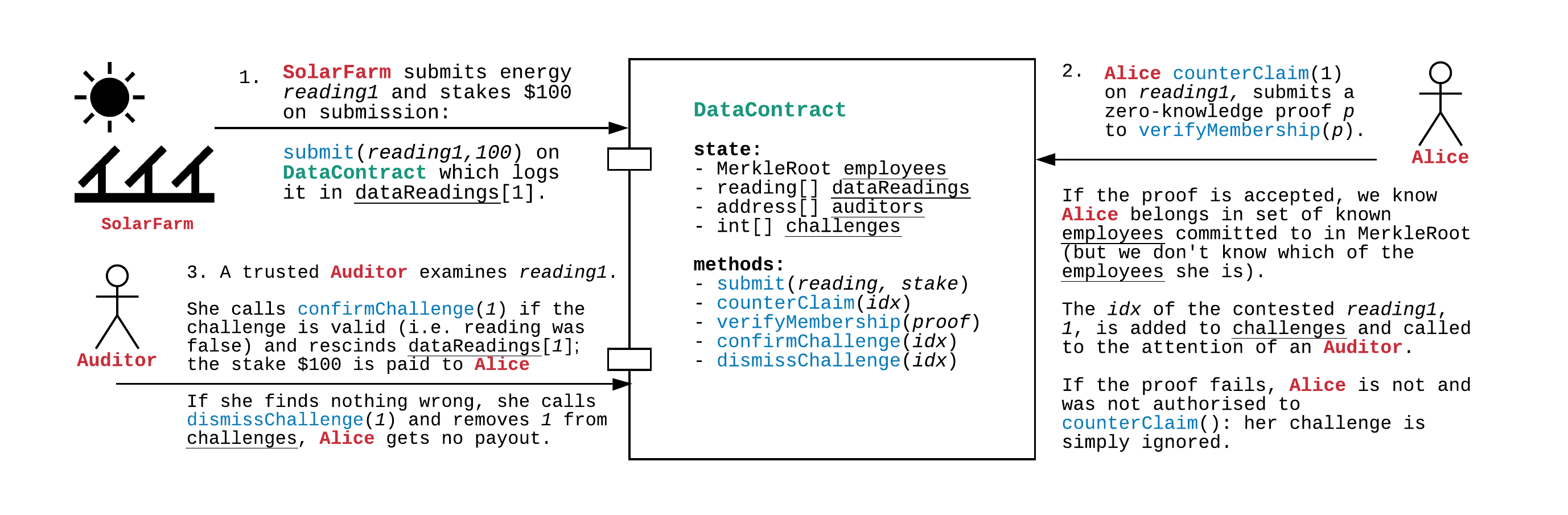

Figure 5. Process flow diagram of a solar energy farm reporting power production data using the PreciDatos system.

We use an example of a solar energy farm which is required to report its daily power production. We also assume that this farm is a corporation with 5 executives. Each executive registers their cryptographic identity into an Ethereum smart contract based on Semaphore, a zero-knowledge signalling gadget, so that anyone can anonymously prove their membership in the set and broadcast a counterclaiming signal (Koh, 2019).

We then simulate the following process of the company reporting data, along with a deposit, for five days in a row, and an executive anonymously counterclaiming on data reported on the fifth day. This locks up part of the total deposit. After an investigation (outside the system), an investigator then seizes part of the total amount deposited, and rewards part of the seized funds to a separate address specified by the counterclaimer.

- On day 1, the solar farm publishes their true power readings on a smart contract and deposits 0.1 ETH along with the data.

- The solar farm does the same for days 2, 3, and 4.

- On day 5, however, the solar farm reports false power readings.

- Alice, an executive in the corporation, decides to counterclaim on this false reading. She produces a zero-knowledge proof of her membership in the set of executives, states that the readings of day 5 are fraudulent, and publishes it. Most importantly, the proof does not reveal Alice’s identity.

- The smart contract locks up 0.2 ETH of deposits pending the results of an external investigation.

- We assume that the investigator is a trusted third party. They hold the administrative private key with which they can unlock the farm’s deposit, or trigger the confiscation of said funds. Alice is rewarded a portion of the deposit for correctly counterclaiming, with this portion determined by the rules agreed upon, and saved in the smart contract. In this demo, she is rewarded 0.1 ETH. For the sake of anonymity, we assume that her payout address, specified along with the zero-knowledge proof, is unlinked to the address used to register her identity.

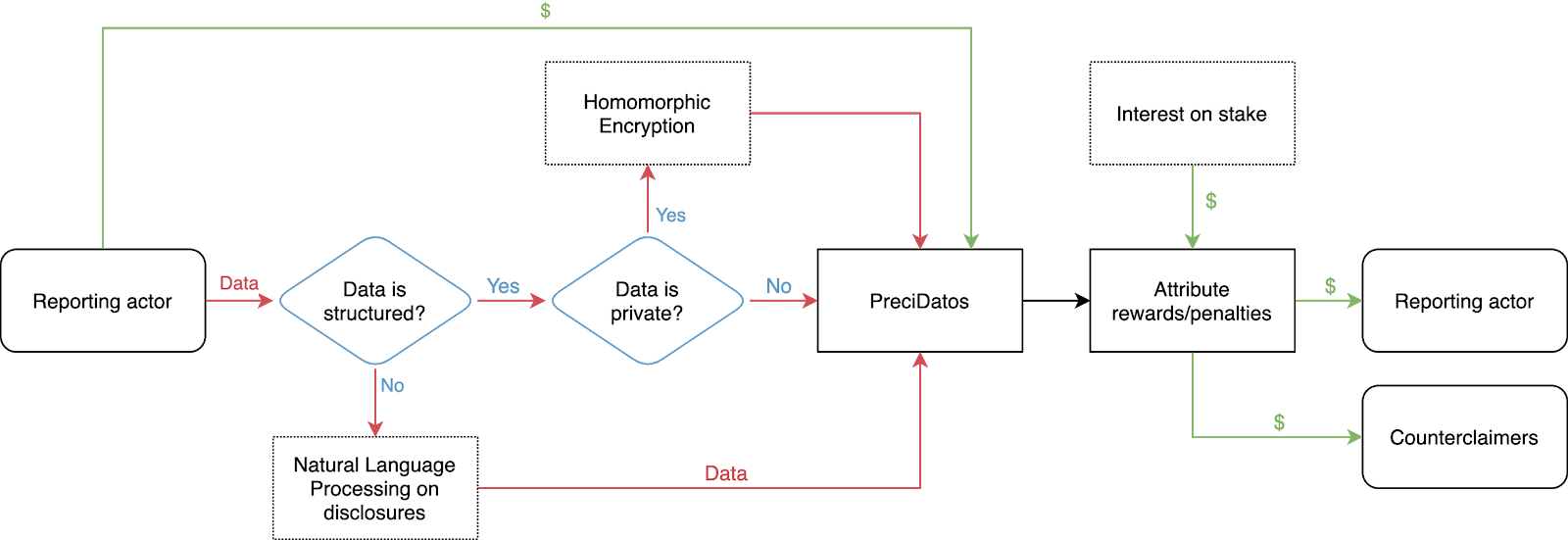

Discussion

PreciDatos is built as a modular component to fit in larger operational processes. In the following, we describe possible extensions to complement our data-reporting mechanism. A modular pipeline proposal is presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Extending PreciDatos with optional modules (dotted blocks).

Natural Language Processing (NLP) of Actor Disclosures

It is not uncommon for actors to upload ill-formed data (e.g., PDFs or spreadsheets produced by an actor’s Corporate and Social Responsibility department). The process of extracting the data from such non-standard formats is time-consuming and costly. PreciDatos may be extended in a modular fashion with a pre-processing step attempting to run Natural Language Processing (NLP) routines to extract semantic information from unstructured data. The module tackles two goals. Firstly, it identifies structured data (e.g., tables) and extracts it as a dataset. Secondly, it performs sentiment analysis to determine the ambition and scope of the document.

The first task can be done with spaCy, an open-source library for NLP in python for tasks such as entity recognition and text processing. It is currently the fastest syntactic parser in the world and within 1% of the state-of-the-art (Choi et al., 2015). It can be trained on existing data to perform automated information extraction. The second task can be conducted with the AllenNLP (Gardner et al., 2017) open-source library which contains reference implementations of state-of-the-art NLP models to extract information from a processed dataset to perform sentiment analysis.

General purpose public blockchains such as Ethereum or Cosmos can run arbitrary programs, as long as the computation is paid for in the native tokens of the chains. While we advocate recording commitments (e.g., a hash of the data) and some reporting progress on a blockchain (as described in the previous Section), NLP routines are computationally intensive, thus ill-suited to be run on the chain. We make the assumption here that a trusted server can commit to the data received initially and perform NLP, after which the resulting data can once again be committed on-chain by the trusted party. The assumption of a trusted party does not appear unreasonable given the centrality of climate databases and institutions (e.g., CDP or UNFCCC).

Homomorphic Encryption

Homomorphic encryption (HE) is a framework allowing for computations on encrypted data. An actor may decide to keep their granular emissions data private (e.g., the CO2 emitted by each factory they own) while releasing their aggregate emissions publicly (e.g., the total of all emissions by all factories). Given only the latter, observers have no choice but to trust that it has been accounted for properly.

Under our proposed HE scheme, actors responsible for their emissions encrypt their granular data. The encrypted data is received by a third-party organization such as CDP. Using HE, CDP is able to run sophisticated checks on the encrypted data without ever gaining access to the true, decrypted data (Homomorphic Encryption Standard, 2017). For instance, an outlier in the encrypted data can trigger an ‘alert’ for further analysis by investigators, without revealing the data itself (Abdulatif et al., 2017). Along with outlier detection, simple statistical checks performed on the encrypted data can reveal inconsistencies (Lu et al., 2016).

The third-party organization hosting the encrypted data can also query and perform computations on the encrypted data, such as aggregating the emissions of various facilities operated by the actor. The results of these queries are then verifiably decrypted by the actor who reveals the aggregate to the third-party organization without revealing the data that forms this aggregate. This procedure provides guarantees for the third-party organization by enabling them to run simple checks on the data provided.

While HE improves upon relying on a single, aggregate number communicated by the actor, encryption does not in itself resolve the issue of inaccurate data, fed as input to the homomorphic computation. However, inaccurate data could be signalled anonymously by counterclaimers with access to the private data, using the PreciDatos module.

As discussed for NLP, we do not expect HE to be performed on a blockchain, given its intensive computational requirements. Once again, we rely on the assumption of a trusted party performing the computation, with on-chain commitments to a public chain.

Security

For the sake of simplicity, we have not implemented features which would be crucial to the security of the system. A more sophisticated system would require that the counterclaimer’s payout address be part of the signal, so that without the counterclaimer’s private key, an attacker cannot substitute their own address and frontrun the transaction. Secondly, we would use a multi-party computation ceremony to securely generate the proving and verifying keys for the zero-knowledge proof. Finally, the system would require counterclaims to deposit funds along with each proof as a bond which the investigator may seize if they find evidence of a fraudulent report. This would disincentivize participants from making such reports.

Staking Disincentives

Companies may choose not to participate in a consortium in which they need to stake – effectively lock up their funds – in order to participate. Their rationale for this may take many forms – they do not possess enough funds, they view it as a potential loss, it creates a strain on cash flow. For this system to work, however, staking is crucial, and thus cannot be removed, even in light of these valid concerns. The heavy-handed approach to this would be coercion, for example through legislation by the state or territory, which is less than ideal. A system works best when participants in it are self-motivated.

A better approach would be through incentivization. In PreciDatos’ specifications, staked amounts are earned back by honest participants. To incentivize participation, some form of interest, competitive with respect to risk-free placements, could be provided. This makes the act of staking itself rewarding, and can be modelled using bond curves with interest rates.

The additional funds to pay for these extra amounts must come from somewhere. We advocate the use of climate-specific funds (e.g., carbon offsets) to invest and reward honest participation in the system. However, under our modular approach, PreciDatos remains agnostic to the provenance of funds and it is possible that different specifics will work for different consortia and different industries.

Physical World vs. Digital World

A key challenge and limitation of this system is that of real world data crossing the boundary into a computer system. If that point of entry is corruptible, it introduces a potential source of failure for the entire system. Care must be taken to ensure proper digital security, for example key management practices. Likewise, care must be taken to physically secure the input devices and sensors used to collect data. The best digital security cannot overcome lapses in physical-world security, as garbage input results in garbage output.

Payment Rules

Companies participating in a consortium are incentivized directly proportional to the work that has been done. A linear scale, while simple to implement and reason about, does little to incentivize increased commitments or higher targets. Consortia that desire their members to increase their commitments might thus do well to alter their payment calculation rules to incorporate some form of target based or commitment based bonus tier. As with the previous section, the exact design of these incentivization structures are left as a discussion for the readers and implementers of this system, as different specific will work for different consortia, and different industries. For rewards, we advocate the use of climate-specific funds (e.g., carbon offsets) to incentivize honest participation in the system.

Glossary

Blockchain is a particular type of data structure used in some distributed ledgers which stores and transmits data in packages called “blocks” that are connected to each other in a digital “chain”. Blockchain employs cryptographic and algorithmic methods to record and synchronize data across a network in an immutable manner (Natarajan et al., 2017).

Bounty is a sum paid out for a particular task done. This can be done through fiat money or tokens inherent to the ecosystem.

For something to be cryptographically-secure, it has to be verifiable through cryptographic techniques.

For something to be cryptographically-verifiable, it can be checked through public hashes and computed independently to check that the hashes are accurate.

Digital signature is a process that guarantees that the contents of a message have not been altered in transit. This is achieved through encryption techniques.

Distributed Ledger Technology refers to a novel and fast-evolving approach to recording and sharing data across multiple data stores (or ledgers). This technology allows for transactions and data to be recorded, shared, and synchronized across a distributed network of different network participants (Natarajan et al., 2017).

Homomorphic Encryption is a form of encryption that allows computation on encrypted data, generating an encrypted result which, when decrypted, matches the result of the operations as if they had been performed on the original data.

Metadata is a set of data that gives information about other data.

On-chain transactions refer to transactions that occur on the blockchain itself. This would be computed using nodes that run the blockchain network.

A signalling gadget is a toolkit to allow users to register an identity, verify it, and create proofs.

Staking is the process of putting up some form of value as a guarantee to a claim.

Tokens are a unit of value issued by the ecosystem and exist in the form of registry entries in the blockchain.

Zero-knowledge proofs are a method by which one party can prove to another party that they know a value x, without conveying any information apart from the fact that they know the value x.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation (Award#1932220; PI: Angel Hsu) and a National University of Singapore Early Career Award (NUS_ECRA_FY18_P15; PI: Angel Hsu).

References

Alabdulatif, Abdulatif, et al. “Privacy-preserving anomaly detection in cloud with lightweight homomorphic encryption.” Journal of Computer and System Sciences 90 (2017): 28-45.

Anderson, J. (2015). What you need to know to complete the CDP Supply Chain questionnaire. Available: https://www.greenbiz.com/article/what-you-need-know-complete-cdp-supply-chain-questionnaire.

Chen, D. (2018). Utility of the blockchain for climate mitigation. The Journal of The British Blockchain Association, 1(1), 3577.

Choi, J. D., Tetreault, J., & Stent, A. (2015, July). It depends: Dependency parser comparison using a web-based evaluation tool. In Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 7th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers) (pp. 387-396).

ClimateSouth (2018). Cooperative Climate Action: Global Performance & Delivery in the Global South. Preliminary findings of the ClimateSouth Project for the Global Climate Action Summit. Research report published by the African Centre for Technology Studies (ACTS), the Blavatnik School of Government and Global Economic Governance Programme at the University of Oxford, the German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), TERI University, prepared by the ClimateSouth Project team: Sander Chan, Thomas Hale, Kennedy Mbeva, Manish Shrivastava, Jacopo Bencini, Victoria Chengo, Ganesh Gorti, Lukas Edbauer, Imogen Jacques, Arturo Salazar, Tim Cholibois, Debora Leao Andrade Gouveia, Jose Maria Valenzuela.

Coburn, C. (September 8, 2019). Why industry is going green on the quiet. The Guardian. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/science/2019/sep/08/producers-keep-sustainable-practices-secret.

Data-Driven EnviroLab. (2019). National Science Foundation Grant will Support Research on Blockchain’s Potential Climate Action Applications. Available: https://datadrivenlab.org/projects/national-science-foundation-grant-will-support-research-on-blockchains-potential-climate-action-applications/.

Data-Driven EnviroLab. (2020). Collaboration gets Radical at COP-25: Digital Solutions to Tracking Climate Action. Available: https://datadrivenlab.org/climate/collaboration-gets-radical-at-cop-25-digital-solutions-to-tracking-climate-action/.

Fong, W. K., Sotos, M., Michael Doust, M., Schultz, S., Marques, A., & Deng-Beck, C. (2015). Global protocol for community-scale greenhouse gas emission inventories (GPC). World Resources Institute: New York, NY, USA. https://ghgprotocol.org/greenhouse-gas-protocol-accounting-reporting-standard-cities.

Gardner, M., Grus, J., Neumann, M., Tafjord, O., Dasigi, P., Liu, N., … & Zettlemoyer, L. (2018). Allennlp: A deep semantic natural language processing platform. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.07640.

Herweijer, C., Waughray, D., & Warren, S. (2018). Building Block(chain)s for a Better Planet. In World Economic Forum. Available: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Building-Blockchains.pdf.

Höhne, N., den Elzen, M., Rogelj, J., Metz, B., Fransen, T., Kuramochi, T., Olhoff, A., Alcamo, J., Winkler, H., Fu, S., Schaeffer, M., Schaeffer, R., Peters, G.P., Maxwell, S. and Dubash, N.K. (2020). Emissions: world has four times the work or one-third of the time. Nature.

Homomorphic Encryption Standard (2017). Applications of Homomorphic Encryption, pp. 5-6. David Archer and Lily Chen and Jung Hee Cheon and Ran Gilad-Bachrach and Roger A. Hallman and Zhicong Huang and Xiaoqian Jiang and Ranjit Kumaresan and Bradley A. Malin and Heidi Sofia and Yongsoo Song and Shuang Wang. Available: http://homomorphicencryption.org/white_papers/applications_homomorphic_encryption_white_paper.pdf.

Hotten, R. (10 December 2015). Volkswagen: The scandal explained. BBC News. Available: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-34324772.

Hsu, A., Cheng, Y., Xu, K., Weinfurter, A., Yick, C., Ivanenko, M., Nair, S., Hale, T., Guy, B., and Rosengarten, C. (2015). The Wider World of Non-state and Sub-national Climate Action. Available: https://datadrivenlab.org/featured/assessing-the-wider-world-of-non-state-and-sub-national-climate-action/.

Hsu, A.; Widerberg, O.; Weinfurter, A.; Chan, S.; Roelfsema, M.; Lütkehermöller, K. and Bakhtiari, F. (2018). Bridging the emissions gap – The role of nonstate and subnational actors. In The Emissions Gap Report 2018. A UN Environment Synthesis Report. United Nations Environment Programme. Nairobi.

Hsu, A., Höhne, N., Kuramochi, T., Roelfsema, M..Weinfurter, A., Xie, Y., Lütkehermöller, K., Chan, S., Corfee-Morlot, J., Drost, P., Faria, P., Gardiner, A., Gordon, D.J., Hale, T., Hultman, N.E., Moorhead, J., Reuvers, S., Setzer, J., Singh, S., Weber, C., Widerberg, O. (2019). A Research Roadmap for Quantifying Non-State and Subnational Climate Action. Nature Climate Change, 9: 1–17.

Hsu, A., Khoo, W., Goyal, N. and Wainstein, M. (In Submission). Next-generation Digital Ecosystem for Climate Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery: A Review of Digital Data Collection Technologies.

Kennedy, C., Steinberger, J., Gasson, B., Hansen, Y., Hillman, T., Havranek, M., … & Mendez, G. V. (2009). Greenhouse gas emissions from global cities. Environmental Science Technology, 43: 7297–7302.

Koh, W. (2019). To Mixers and Beyond: presenting Semaphore, a privacy gadget built on Ethereum. Available: https://medium.com/coinmonks/to-mixers-and-beyond-presenting-semaphore-a-privacy-gadget-built-on-ethereum-4c8b00857c9b.

Lu, Wenjie, Shohei Kawasaki, and Jun Sakuma. “Using Fully Homomorphic Encryption for Statistical Analysis of Categorical, Ordinal and Numerical Data.” IACR Cryptology ePrint Archive 2016 (2016): 1163.

Markolf, S. A., Matthews, H. S., Azevedo, I. L., & Hendrickson, C. (2017). An integrated approach for estimating greenhouse gas emissions from 100 US metropolitan areas. Environmental Research Letters, 12(2), 024003.

Nakamoto, S. (2008). Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system. Available: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf

Natarajan, Harish; Krause, Solvej Karla; Gradstein, Helen Luskin. 2017. Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) and blockchain (English). FinTech note; no. 1. Washington, D.C. : World Bank Group. Available: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/177911513714062215/Distributed-Ledger-Technology-DLT-and-blockchain.

NewClimate Institute, Data-Driven Lab, PBL, German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford. Global climate action from cities, regions and businesses: Impact of individual actors and cooperative initiatives on global and national emissions. 2019 edition. Research report prepared by the team of: Takeshi Kuramochi, Swithin Lui, Niklas Höhne, Sybrig Smit, Maria Jose de Villafranca Casas, Frederic Hans, Leonardo Nascimento, Paola Tanguy, Angel Hsu, Amy Weinfurter, Zhi Yi Yeo, Yunsoo Kim, Mia Raghavan, Claire Inciong Krummenacher, Yihao Xie, Mark Roelfsema, Sander Chan, Thomas Hale. Available: https://datadrivenlab.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Report-Global-Climate-Action-from-Cities-Regions-and-Businesses_2019.pdf.

Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability (PBPS). (2015). Climate Action Plan. Available at: https://beta.portland.gov/sites/default/files/2019-07/cap-2015_june30-2015_web_0.pdf.

Power Ledger. (2020). Power Ledger: Our Technology. Available: https://www.powerledger.io/our-technology/

Bhatia, P., Ranganathan, J., and World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD). (2004). The Greenhouse Gas Protocol: A Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard (Revised Edition). Available: https://www.wri.org/publication/greenhouse-gas-protocol.

Ramankutty, N., Gibbs, H. K., Achard, F., Defries, R., Foley, J. A., & Houghton, R. A. (2007). Challenges to estimating carbon emissions from tropical deforestation. Global change biology, 13(1), 51-66.

Rust, S. (25 September 2019). Poor corporate emissions data ‘a scandal’, says analysis firm. IPE. Available: https://www.ipe.com/poor-corporate-emissions-data-a-scandal-says-analysis-firm/10033469.article.

Swytchx. (2019). Swytchx Platorm: A new standard for energy data. Available: https://swytch.io/products

United Nation Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). (2017). How Blockchain Technology Could Boost Climate Action. Available: https://unfccc.int/news/how-blockchain-technology-could-boost-climate-action.

United Nation Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). (2020). Global Climate Action Platform: https://climateaction.unfccc.int/.

Wainstein, M. (2019). Leveraging blockchain for a global, transparent and integrated climate accounting system. Available: https://07579f97-57bc-4895-8632-76beebc72c0e.filesusr.com/ugd/9909c7_8ee2e5519ba94d55a24f3445082edd50.pdf.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks