The case for biking in fostering healthy behaviors and favoring equity in vulnerable settings – Montréal, Canada.

The case for biking in fostering healthy behaviors and favoring equity in vulnerable settings – Montréal, Canada.

Article written by Morgane Ollier and Genévieve Westgate.

Introduction:

Indices such as the Copenhagenize Bicycle Friendly Cities Index1See Copenhagenize Bicycle Friendly Cities Index. which rank cities on their biking performances, have pushed planners to re-assess the potential of active mobility as a viable solution to the pressing environmental challenges of the transportation sector. In light of current sustainability efforts to promote active transportation, this case study questions the implications of biking on health and social well being, as well as social justice. Montréal is among the most bike-friendly cities in North America, however, is it really bike-equitable?

1. The implications of biking on health and related well being:

Physical inactivity is one of the most important global health challenges due to its impact on common deadly chronic diseases, most notably overweightness and obesity, which are responsible for 2.8 billion deaths2OECD/International Transport Forum. Cycling, Health & Safety. OECD Publishing. (2013). annually, worldwide. The type of transportation chosen will undoubtedly have an impact on levels of physical activity in urban areas. While using a car may inhibit physical activity, cycling — even for just 30 minutes a day — may have numerous beneficial health outcomes, such as reduced rates of obesity, cardiovascular disease, certain forms of cancer, and depression.3OECD/International Transport Forum. Cycling, Health & Safety. OECD Publishing. (2013). Moreover, biking has been found beneficial to mental health, by means of social integration and feelings of belonging. In fact, as stated by Thoreau,4Mackett R L, and Thoreau R. Transport, social exclusion and health. (2015). “access to [a] transport system allows individuals to participate in many aspects of society.” As biking increasingly becomes a solution to daily commuting behaviors, the emphasis on understanding its relationship to feelings of belonging and well being is fundamental.

2. Why is health important in the discussion on equity?

Socio-economic disparities in health status reflect underlying inequities in the distribution of “primary goods”, that is, opportunities, income, wealth, and the social basis for respect. In Montréal and other cities, there is evidence that the state of health still very much depends on socio-economic status. Most significantly, life expectancy in wealthier neighborhoods is much higher than in lower income neighborhoods — this disparity can often be as large as 10 years. These health inequalities are not just limited to life expectancy, but also to infant mortality, mental health and physical health. In fact, the high rate of obesity in some Eastern neighborhoods of Montréal such as Saint Léonard-Saint Michel (21.2 percent, compared to the Montréal average of 17.0 percent) is highly correlated with the level of income.5Centre Intégré Universitaire de Santé et Centres Sociaux du Centre Sud. Enquête québécoise sur la santé de la population. (2014-2015). These health inequalities imply that not everyone can reach their full potential of leading a flourishing and healthy life. Children who were born with a health problem have been found to be less successful in school, potentially leading to long term negative returns, such as difficulties in joining the skilled workforce and associated economic burdens.6Leblanc, Marie-France, Raynault Marie-France. Les inégalités sociales de santé à Montréal : le chemin parcouru. 2ème édition. Rapport du directeur de Santé Publique. (2012). As such, health inequity and socio-economic status are interconnected and mutually reinforcing. Achieving equity is multifactorial; however, eliminating health disadvantages by favoring daily healthy practices such as biking can have visible ripple effects on accessing opportunities and resources.

3. Active transportation and social justice: can biking policies marginalize the most vulnerable?

There has been very little research on the social implications of active transportation on the most disadvantaged communities until recently. Some anthropological works have, however, emphasized interesting correlations between the social perception of bikes and related socio-economic status or cultural attributes of certain groups. As a matter of fact, bikes are often associated with the idea of deprivation and precariousness, and cyclists7Willis, D., Manaugh, K., & El‐Geneidy, A. (2015). Cycling under influence : Summarizing the influence of attitudes, habits, social environments and perceptions on cycling for transportation. International Journal of Sustainable Transportation, 9 (8), 565‐ 579. can feel concerned about the way they are socially disregarded.

Moreover, many groups and communities do not have the capacity to use bikes for endogenous reasons such as physical disabilities, cultural, or gender dimensions. More women than men say that they do not use public transit because they feel unsafe, and they face difficulties carrying out several activities, such as commuting between children’s schools and the workplace.8Leblanc, Marie-France, Raynault Marie-France. Les inégalités sociales de santé à Montréal : le chemin parcouru. 2ème édition. Rapport du directeur de Santé Publique. (2012). Disjointed policies that do not address people’s specific needs can thus reinforce social marginalization and exacerbate a sense of isolation.

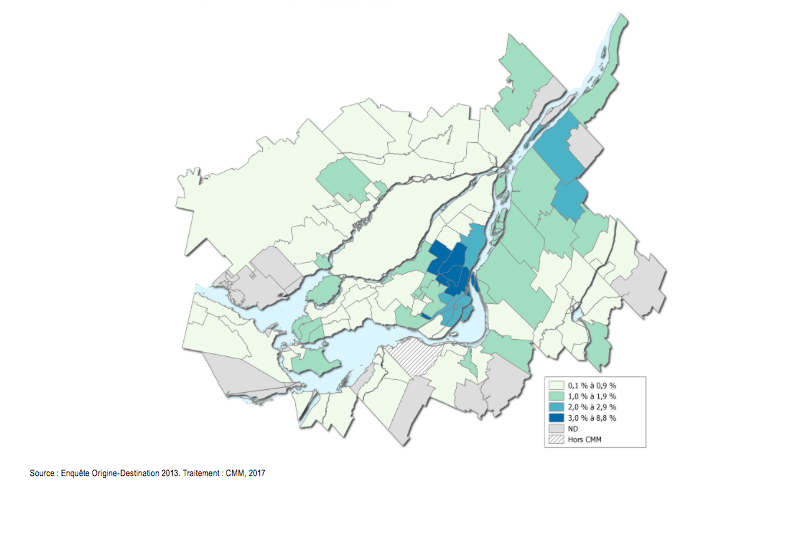

Lastly, spatial disparities in Montréal, as indicated by the concentrated location of 58 percent of Montréal cyclists in just five neighborhoods,9Godefroy, F. Méthodologie de caractérisation du vélopartage et d’estimation du marché potentiel du vélo à Montréal de maitrise. Ecole Polytechnique Montréal. (2011). (Villeray, Rosemont, Le Plateau, le Centre Ville and Montréal South-East, the most central boroughs) emphasize social injustice. Many disadvantaged communities are located in secluded areas, substantially lacking access to alternative mobility means. Without a car or adequate transit servicing, many people find themselves extremely reliant on others (especially the elderly), or in a state of isolation, away from activity centers and places of encounters. Here, bikes could provide an opportunity for these people to get around and access services and resources more easily. In Montréal, one can observe this clear disconnect between the current locations of public bikes, and the places where they may be most needed.

On the other hand, active transportation comes with its share of socio-spatial tensions: negative cultural perceptions, spatial injustices (centralization of services in centers favoring central bike paths), and a resulting lack of equity in alternative transit offerings and opportunities between groups. Considering that a fair share of people are economically disadvantaged and do not get around the city by car, access to services and opportunities that match each of residents’ needs by alternative means of mobility such as biking is all the more crucial, and needs to be addressed coherently.

Figure 1. Modal share of bike trips in the greater Montréal, according to neighborhoods/municipalities of trip origin during Fall 2013. Source: Communauté Métropolitaine de Montréal (CMM). 2017

4. Planning for green active mobility in Montréal: an inclusive or discriminatory landscape?

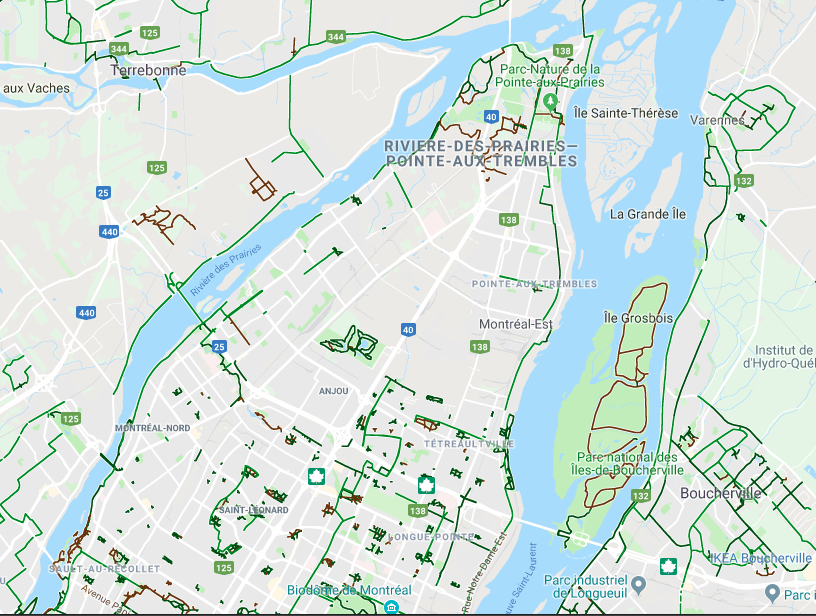

While the number of cyclists registered in Montréal has been increasing over the past 10 years, growing as rapidly as 60 percent in the past five years, important neighborhood disparities in terms of bike paths and infrastructure remain.10Gaïor Camille, Les cyclistes et les déplacements en hausse en 2015. TVA Nouvelles Website. 2016 Taking a quick look at Pédal Montréal’s index11See Pedal Montréal reveals that streets designed for bikes, bike lanes, or BIXI (public bike-share system) stations are much more present in high-income neighborhoods such as Westmount (which has an average income of 186,567 USD) than in low-income neighborhoods such as Lachine (51,636 USD) or Lasalle (47,699 USD), taking into account the equal distance of such neighborhoods from the city centre. Population density in low-income boroughs such as Rivière-des-Prairies also raises questions about the lack of biking lanes and infrastructure in highly populated areas of the city. Taking a closer look at Montréal’s bike-share program (BIXI), considered one of North America’s most reputable public bike-share systems with 540 stations,12Vélo Quebec. L’état du Vélo à Montréal en 2015. (2016). one can observe the disproportionate lack of bike offerings in some of the poorest neighborhoods of the city with relatively high population densities (namely Montréal North or Rivière des Prairies; see figure 2). The remoteness of these districts from the city centre seems to be an invalid vindication for the lack of bike infrastructure since population densities are some of the highest in comparison to some wealthier, less populated neighborhoods in the West, that have bike-lanes.

Figure 2. A map of bike lanes in Montréal reveals a lack of biking infrastructure in low-income neighborhoods, particularly Montreal East, Anjou, Montréal Nord, Saint Leonard and Rivière des Prairies. Source: Pedal Montréal.

5. Conclusion:

The potential of bikes to revolutionize transportation and mobility patterns is increasingly recognized and included in sustainability plans to meet GHG targets. Likewise, the potential of bikes to foster increased equity, whether on health criteria, or in people’s ability to access resources and services offered by the city, has also become clearer. Biking has been found to have large positive returns on health, and increased physical activity leads to a decrease in related diseases. It can also act as a determinant of social well being, favoring feelings of belonging by facilitating movements across the land, while increasing citizens’ participation in urban activities and amenities, such as access to employment, education, as well as green spaces. However, these assumptions can only hold true for all urban residents, including the most vulnerable (whether socially, physically or economically disadvantaged), if they guarantee equity in biking usage. For this specific reason, stakeholders from private, public and non-state actors that favor biking as a green alternative to transit, need to consider equity as a crucial determinant of policy success. Considering this matter through the prism of social justice will help make biking a plausible transportation solution in tomorrow’s sustainable world. To achieve these goals, cities can learn from initiatives such as San Francisco’s Multicultural Communities for Mobility program, which ran information campaigns and round tables among low-income communities and people of color on their right to use bicycles and public bike-share offerings. By informing these communities on the existence of biking systems as well as their ability to appropriate bikes as their mode of commuting, the groups at most disadvantage became included in the shift towards more sustainable lifestyles, paving the way towards more sustainable and inclusive cities.

unfortunately your link to http://www.pedalmontreal.ca goes to a domain sales site. Good report though.

thanks for pointing this out – it’s fixed now.