Earlier this summer, I packed my bags and headed off to three cities in Laos – Luang Prabang, Vang Vieng, and Vientiane – and to Bangkok, Thailand. The main goal of this fieldwork was to collect data on land-use across cities in Southeast Asia. This work will support Data-Driven Lab director Dr Angel Hsu’s efforts to study urbanization trends and their environmental impacts in Southeast Asia, via tools such as satellite imaging. Visiting these cities in-person to collect data on land-use change allows me to ground-truth initial findings that are only based on satellite imagery. This data will help shed light on the drivers of land-use change and urban expansion within Southeast Asia, information integral to creating more informed urban sustainability policies.

Ground-truthing land-use classifications

Land-use classifications, as the name suggests, allows researchers to determine a site’s usage(s) and answer questions such as: is the demarcated plot of land used for residential, leisure, commercial, agricultural, or tourism purposes? How has the usage of this plot of land changed over time? This helps researchers measure how residents engage with the city they live in, and understand how a particular community respond to different stimulants such as an influx of foreign investments or migration, etc.

Satellite imagery is a useful tool to tease out preliminary deductions about a specified area’s land-use. However, the nature of a satellite image – a top-down bird’s eye view of an area, often at a relatively coarse spatial resolution – prevents satellite imagery from acting as a definitive piece of evidence. For example, the land-use classification of the image below is ambiguous; researchers cannot discern if it serves residential and/or commercial purposes. By visiting these kinds of sites in-person, researchers can corroborate or disambiguate the initial deductions of land-cover use based on satellite imagery. Over time, this type of “ground-truthing” can help develop algorithms that researchers can use to interpret satellite imagery more accurately.

An ambiguous satellite image that does not provide enough clarity for us to assert the land-use of the area confidently; i.e., we do not know whether it is used for residential or commercial purposes.

For example, the image below is the street-level view of the image seen from an aerial view in the picture above. The presence of restaurants, vehicle repair shops, and mini-marts indicates that this site is used for commercial purposes.

At the end of the ground-truthing exercise, there were multiple points in the dataset whose street-level assessment yielded different observations from the initial land-use assessment that were solely based on satellite imagery. These findings will ultimately form part of the preliminary dataset that Dr. Hsu and her team will use to create an algorithm that helps sharpen the interpretation of satellite images.

On a more personal level, this exercise has shown me that it is essential to think critically about claims made solely based on satellite imagery, as it does not necessarily paint a completely accurate picture.

Rapid rates of land-use change in Southeast Asia

The study of land-use change is particularly salient in Southeast Asia, where, according to the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, close to 50% of the region’s people will live in an urbanized area by 2025. The impacts of such rapid rates of urbanization within Southeast Asia will be studied by many via the lens of sustainability and inclusivity. The presence of such an increasing degree of scrutiny motivated the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to enact the ASEAN Sustainable Urbanization Strategy in 2018.

One primary driver of urbanization within Southeast Asia is Chinese investment. Since the 1990s, there has been a massive influx of cross-border trade and investments from China. Bilateral trade between ASEAN nations and China ballooned from 7.96 billion USD in 1991 to 72 billion USD in 2015 – with the two entities estimating bilateral trade figures of 1 trillion USD by 2020.

A prominent case study of Chinese investments is China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which is the latest driver of investments in Laos and the other Southeast Asia countries. Introduced in 2013 by China’s president Xi Jinping, the BRI is a trillion dollar (and growing) developmental initiative that focuses on infrastructure development and direct investments between China and 65 other countries. This initiative connects Asia, Africa, and Europe through land routes – the Silk Road Economic Belt – and Southeast Asia routes – the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road. The land route connects 6 mainland economic corridors: New Eurasian Land Bridge, China-Mongolia-Russia, China-Central Asia-West Asia, China-Indochina Peninsula, Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar, and the China-Pakistan corridor.

Within SEA, the China-Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor captures an extensive transportation network of railroads and highways and a series of industrial projects. Notably, China’s infrastructure development projects in Southeast Asia primarily occurs in the energy, transport, and real estate sectors. Given that such projects require plenty of land to be constructed on, the potential outcomes can vary in terms of spillover effects. On the one hand, there could be positive spillover effects for the locals in terms of employment opportunities; on the other, there could be an abrupt displacement of locals.

Given that the projected impacts of Chinese-backed infrastructure development projects on urban land-use change are currently understudied, I am excited and grateful for the opportunity to contribute to this new area of academic literature.

First-hand exposure to urban developments in Laos

My fieldwork included visiting more than 100 randomly generated data points that were dispersed throughout all four cities, so I had the privilege to visit places that are experiencing different rates of change.

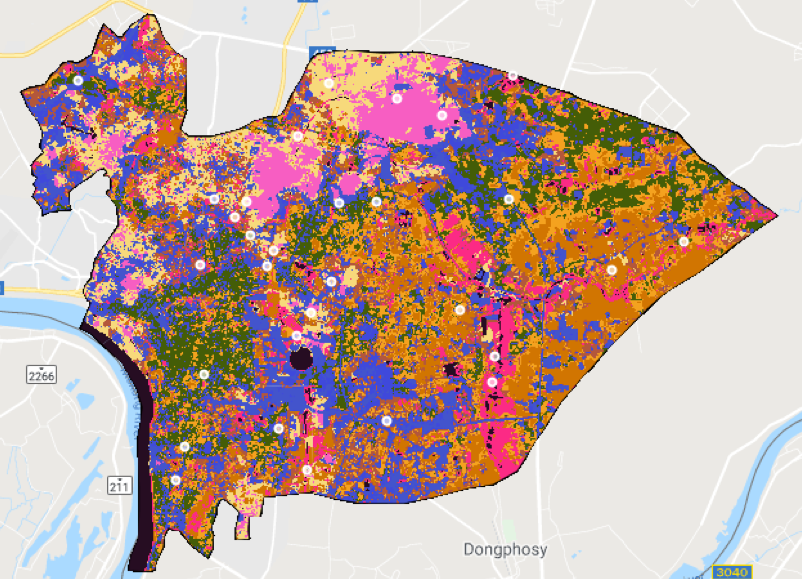

In this image of Vientiane, the random sample of white dots represent the sites where I conducted the

ground-truthing exercise. This image was produced with the aid of Google Earth Engine.

Concerning the impacts Chinese investments have on Laos, two case studies that I visited come to mind: the Laos-China railway and the That Luang Lake Specific Economic Zone (SEZ).

The Laos-China Railway

The Laos-China railway is a 414-kilometer physical manifestation of the BRI that aims to link Kunming, Yunnan’s provincial capital, and Vientiane, Laos’ capital city, by December 2021. This enormous engineering endeavor will shorten the travel time between the two cities from 3 days to 3 hours, according to Lao Railways’ director general Somsana Ratsaphong.

The Laos-China Railway in Luang Prabang. According to Mr. Tang, construction work on these 47-meter tall concrete pylons started last February. He aims to finish connecting all these pylons by October 2019. Photo credit: Jacob Jarabejo.

During my fieldwork, I met with Jessica DiCarlo, a PhD Candidate in the Geography department at the University of Colorado Boulder. Jessica brought me to meet Mr. Tang, the project manager of the Laos-China railway, who is part of the China Railway No.8 Engineering Group (中国中铁股份有限公司).

Mr Tang, project manager of the Laos-China Railway, and I amidst the series of concrete pylons. Photo credit: Jacob Jarabejo.

Based on my conversations with Mr. Tang, I discovered that the firm plans to finish the segment of the railway found in Luang Prabang by October this year. Currently, there are over 400 Chinese workers – no numbers were given for locally-hired workers – constructing this segment of the railway at Luang Prabang.

The entire railway is expected to be completed by the end of this year. Mr. Tang also shared that he is in talks with investors about the creation of a new small town, Luang Prabang New City (琅勃拉邦新城), located in the vicinity of the construction site. Construction of this town will begin once the railway is operational, and, hopefully, stimulate economic activity in Luang Prabang.

Given the project’s scale and rapid rate of construction, it is indeed an engineering marvel. However, several controversies and concerns also surround this project.

The Lao government’s ability to finance the Laos-China railway, which costs approximately $6 billion USD, has raised concerns. The planned financing structure of the railway is serviced by a 30/70 joint venture between state and private actors from Laos and China. Currently, the Lao government is only servicing 30 percent of its 30 percent share ($250 million USD out of $715 million USD) of the joint venture through funds from its national budget; the other 70 percent of its share is being financed by loans from the Export-Import Bank of China. The Lao government’s readiness to pile on debt amidst its rising debt-to-GDP ratio is worrying.

In 2017, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) increased Laos’ risk of debt distress from moderate to high, which reflects the IMF’s view of the Lao government as increasingly being unable to service their public debt. The thought of a debt default shrouded with the looming clouds of a global recession paints a gloomy picture for Laos’ future economic stability.

Beyond financing concerns, the Laos-China railway project is controversial for reasons such as unequal employment opportunities for the local population and the abrupt displacement of local communities. According to a presentation on the BRI and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Laos by Mr. Vanxay Sayavong, Chief of Macroeconomic Monitoring and Forecasting Division for the National Institute of Economic Research (NEI), in 2018, only 4,032 (23%) out of 17,115 workers hired for the construction of the Laos-China railway were locals. Based on these unequal employment figures, it is hard to justify the Chinese media’s portrayal of the construction of the railway as a “win-win cooperation deal” for the local population.

In addition, to facilitate the construction of the railway by 2021, Laos’ Ministry of Public Works and Transports estimates that approximately 4,400 families will be displaced from their current location. Lao Decree no. 84 provides a framework for the compensation and resettlement of the Lao people who are involved in development projects and stipulates that compensation will be offered to displaced families. Yet, a majority of them have not been paid or have been underpaid by the Lao government.

With the influx of foreign Chinese workers who have an increasing influence on Laos’ consumption pattern and the displacement of local communities, solely due to the construction of the railway, the physical landscape seen in Laos is undeniably undergoing a massive transformation. Only time will tell if this transformation is beneficial for the locals. But, based on my observations and current public data, it does seem like the benefits are asymmetrical.

The That Luang Lake Specific Economic Zone (SEZ)

A similar story of displacement without proper compensation due to a Chinese-funded construction project exists in the capital city of Laos, Vientiane. A relocation exercise was conducted for the villages located within the demarcated 365 hectares of land that is now known as the That Luang Lake Specific Economic Zone (SEZ). Unfortunately, based on my conversations with some of the people there, it seems that corruption and unjust amounts of compensation surrounds this relocation exercise.

In 2012, construction began in the That Luang Lake SEZ, whose development plans include multiple real estate developments, such as condominiums, a golf course, entertainment centers, and even plans for the area to be a financial and business hub. It is estimated that the SEZ will receive a total of $1.6 billion USD in private Chinese investments over a 15-20-year horizon.

The That Luang Lake SEZ. Seven out of the 12 planned condominiums have been built, and some of the condominiums are already inhabited. The condominiums’ prices range from USD $74,000 to USD $600,000. Photo credit: Jacob Jarabejo.

Though the development is only in its second phase, it has already attracted the attention of scientists who are studying the ecological impacts of the artificially built lake – the giant circle in the satellite image of the site. Researchers I spoke with noted potential disruptions to the surrounding Mekong River. That Luang Lake also lies on top of a natural marsh. With 17 local villages situated around this area, their reliance on the marsh flood protection, water treatment, and resources to sustain themselves could potentially be affected.

My visit to the That Luang Lake SEZ made me realize the importance of an effective urban sustainability policy. Without it, the rate of such construction projects and its impacts on local communities and its surrounding environment tend to go unchecked. And, for better or for worse, this SEZ serves as a compelling case study for changing land-use and its effects on the local communities.

Given that Vientiane is a much more bustling city as compared to Luang Prabang and Vang Vieng, my time spent at the That Luang Lake SEZ felt strangely quiet. There was a jarring contrast in the social environment between the That Luang Lake area, which was expansive yet largely uninhabited, and the rest of Vientiane city. In some ways, the SEZ felt detached from the capital city of Laos.

A graphic depicting the completed That Luang Lake SEZ. Source: Skyscraper City.

Overall, these two case studies – the Laos-China railway and the That Luang Lake SEZ – help illustrate the impacts of rapid urbanization in Laos, and their impacts on the livelihoods of the local communities and the environment. Ground-truthing exercises can tangibly ground some of the potential claims about these kinds of large-scale projects. For example, with the displacement of local communities, is the conversion of a previously residential area into a commercial hub beneficial for the local communities in the long run? If so, how can the government, then, appropriately compensate those displaced local communities such that they will not become the victims of the developmental process. Hence, research of such nature equips policymakers to make more informed decisions as they proceed to integrate foreign investments and urban sustainability and inclusivity.

More details about this research project can be found in this blog post, and more field notes — this time from Cambodia — are available here.

Dear Jacob,

Thank you very much for your exploration on this concerned issue of my country, really appreciated your information and it is very useful for those who do care about these threats. I am conducting a research on labour migration and human trafficking in the northern Laos, now I am searching for some references of the National Committee of the Rail Way project but haven’t yet found any, in case you came across them, please kindly share them with me.

Many thanks and cheers!

Tok