Last month saw the launch of the UN’s “Race to Zero” campaign, which engages an impressive 995 companies, 449 cities, 38 investors, 21 regions, and 505 universities. Together, these actors – which account for 25% of global CO2 emissions and more than 50% of global GDP – have committed to reach net zero CO2 emissions no later than 2050.1Global Climate Action NAZCA.” United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, climateaction.unfccc.int/views/cooperative-initiative-details.html?id=94. The umbrella group comprises a diverse array of actors, encompassing a number of smaller initiatives that range from the Fashion Charter for Climate Action to the Argentinian Network of Municipalities. Not only that, but the Race to Zero Campaign itself is part of a larger coalition, known as the Climate Ambition Alliance, which formed at the 2019 UN Climate Action Summit and includes 120 countries also committed to net zero CO2 emissions by 2050.2“Global Climate Action NAZCA.” United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, climateaction.unfccc.int/views/cooperative-initiative-details.html?id=94.

Indeed, these days everyone seems to be talking about net zero, and the emergence of networks such as the Climate Ambition Alliance is a hopeful sign. Almost inevitably, though, we come to the question of whether these targets will translate to necessary action. There are no easy answers, and to reach any satisfying conclusions, we must first dive into what net zero emissions actually implies and what existing net zero targets look like.

1. Achieving net zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is essential for keeping warming below 1.5° Celsius.

Because net zero targets have only recently begun to take center stage in the global climate action arena, much of the associated jargon is unfamiliar to the general public. One of the first things to know is that a net zero target doesn’t necessarily suggest a complete reduction of all greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Rather, most net zero targets aim for an 80-100% reduction in their emissions impact through a combination of direct reductions and offsets, which typically involve the use of carbon storage or carbon removal techniques (more on those later).

While such goals may seem daunting, it is imperative to understand that net zero emissions globally is not only achievable, but critically important. The UNFCC’s Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C – published in October 2018 – announced that in order to limit warming to 1.5°C or less, “Global net human-caused emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) would need to fall by about 45 percent from 2010 levels by 2030, reaching ‘net zero’ around 2050.”3IPCC, 2018: Summary for Policymakers. In: Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, H. O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J. B. R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M. I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, T. Waterfield (eds.)]. Not only that, but total human-caused greenhouse gas emissions must reach net-zero between 2063 and 2068.

Even if we only aim to limit warming to 2°C – which puts us at a much higher risk of hitting irreversible tipping points – we must achieve net-zero carbon dioxide emissions by 2070, and net zero total GHG emissions by 2100.4J. Rogelj, D. Shindell, K. Jiang, S. Fifita, P. Forster, V. Ginzburg, C. Handa, H. Kheshgi, S. Kobayashi, E. Kriegler, L. Mundaca, R. Séférian, M. V. Vilariño, 2018, Mitigation pathways compatible with 1.5°C in the context of sustainable development. In: Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, H. O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J. B. R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M. I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, T. Waterfield (eds.)]. Achieving net zero emissions globally is not an overambitious goal or a fanciful dream. It is a necessity for preventing climate catastrophe.

2. Overreliance on carbon offsetting to achieve net zero GHG emissions can be dangerous.

Realizing this goal of net zero emissions globally will only be possible through a combination of direct emissions reductions and offsets. However, while offsets have an important part to play in the race to net zero, actors should be wary of relying too much on them. Carbon offsetting encompasses a wide variety of practices that are used to “cancel out” any emissions that remain after actors have reduced what they can. These practices range from land-based approaches – essentially, carbon sequestration in natural sinks such as forests and soil – to carbon dioxide capture and storage using human technologies. While some techniques in this latter category are operable today, many are still under development or not ready for deployment on a large-scale. By relying on currently undeveloped technologies to achieve their net zero targets, actors ignore the need – and their ability – to pursue deep decarbonization in the immediate future.

In their report Climate Emergency, Urban Opportunity, the Coalition for Urban Transitions explains that “deploying low-carbon measures in cities could reduce greenhouse gas emissions from urban building, materials, transport and waste by nearly 90% by 2050.”5Colenbrander, Sarah & Lazer, Leah & Haddaoui, Catlyne & Godfrey, Nick. (2019). Climate Emergency, Urban Opportunity: How national governments can secure economic prosperity and avert climate catastrophe by transforming cities. These measures, all of which are technologically-feasible, highlight the need to shift away from offsets and focus our attention on decarbonization as a means of reaching net-zero emissions.

All this being said, every pathway that limits warming to 1.5°C relies on carbon removal technologies to eliminate somewhere between 100 and 1000 Gigatons of CO2 from the atmosphere over the course of this century.6 IPCC, 2018: Summary for Policymakers. In: Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, H. O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J. B. R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M. I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, T. Waterfield (eds.)]. Therefore, actors should ensure that where they must employ carbon offset projects, they do so effectively and responsibly. The C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group’s Carbon Neutrality Guidance for Cities explains that “in order for carbon credits to contribute to a city’s carbon neutral goals, [the associated offsets must be] real, additional, permanent, measurable, independently audited and verified, unambiguously owned and transparent.”7C40 Cities, April 2019. Defining Carbon Neutrality for Cities & Managing Residual Emissions – Cities’ Perspective & Guidance.

3. Different actors mean different things when they talk about “net zero.”

Much in the same way different actors take different paths to net zero, different actors define net zero differently. “Net zero” is typically treated as a phrase with a single, universally-understood meaning, but the reality is that when actors commit to achieving net-zero emissions, they might be referring to any number of distinct goals. For starters, a target of net-zero emissions can refer to carbon dioxide emissions, specifically, or greenhouse gas emissions more broadly. Moreover, different net zero targets cover different ranges of emissions.

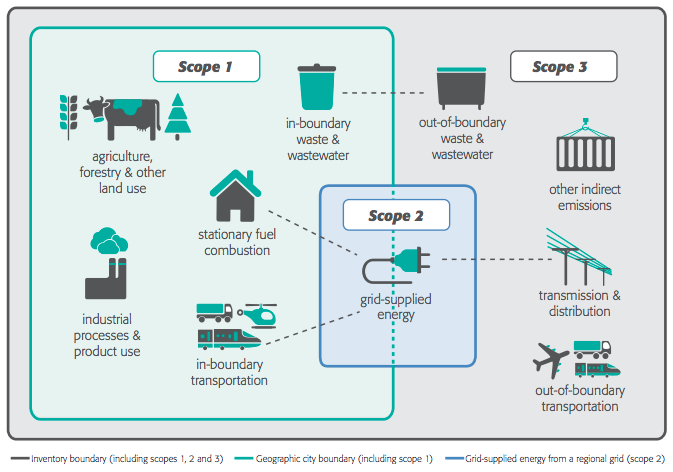

Actors’ emissions are categorized into three scopes: Scope 1 emissions directly originate in actors’ activities, Scope 2 emissions are those involved in the production of electricity for actors’ activities, and Scope 3 emissions are all other emissions generated outside actors’ accounting boundaries for activities within their accounting boundaries (basically, in their supply chains).

A diagram outlining scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions for urban actors, sourced from the Global Protocol for Community-Scale Greenhouse Gas Emission Inventories: An Accounting and Reporting Standard for Cities.

Actors with varying levels of ambition set targets that cover different scopes of emissions, and sometimes even cover different scopes for different activities. However, most of the variation among targets is at the level of Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions; very few actors have attempted to even quantify, much less eliminate, their Scope 3 emissions.8World Economic Forum, 2019, The Net-Zero Challenge: Global Climate Action at a Crossroads (Part 1). This is perhaps unsurprising given that Scope 3 emissions encompass sectors, such as aviation, with impacts that are much more challenging to measure and control.

In the realm of cities, one of the most common definitions of net zero is established by the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group, which requires that a city demonstrate at minimum:

- Net-zero GHG emissions from fuel use in buildings, transport, and industry (scope 1)

- Net zero GHG emissions from use of grid-supplied energy (scope 2)

- Net zero GHG emissions from treatment of waste generated within city boundary (scope 1 + scope 3)9C40 Cities, April 2019. Defining Carbon Neutrality for Cities & Managing Residual Emissions – Cities’ Perspective & Guidance.

While there is less consensus among companies about what a net zero target should look like, many form networks – sometimes in partnerships with governments and civil societies – that provide guidance and unity. The Business Ambition for 1.5°C campaign, for example, requires that all participating companies “set science-based targets aligned with limiting global temperature rise to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.”10 “Business Ambition for 1.5°C: UN Global Compact.” UN Global Compact: Uniting Business for a Better World, UN Global Compact, unglobalcompact.org/take-action/events/climate-action-summit-2019/business-ambition.

4. Current ambition may not be enough…

Although the emergence of initiatives such as the Business Ambition for 1.5°C campaign is encouraging, recent reports suggest that current ambition is insufficient for limiting warming to 1.5°C or less. The 2019 UNEP Emissions Gap Report found that “[i]n 2030, annual emissions need to be 15 GtCO2e lower than current unconditional [nationally-determined contributions] imply for the 2°C goal, and 32 GtCO2e lower for the 1.5°C goal.”11UNEP (2019). Emissions Gap Report 2019. Executive summary. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi. At the time of its publication, an increasing number of countries were proposing net zero commitments, but few had actually drafted a comprehensive timeline for achieving this goal. No G20 members had submitted such timelines; in fact, notably absent from the list of actors with net zero targets in any form are the United States, China, and India – the world’s three biggest greenhouse gas emitters.

While the 2019 UNEP Emissions Gap Report focused only on climate action at the national level, other analyses suggest that efforts at the subnational level are nowhere near enough to compensate. The 2019 Global States and Regions Annual Disclosure report announced that while many of its 124 reporting governments were close to reaching their 2020 targets, “projection analysis ha[d] already shown that states and regions are not in line with the 1.5°C trajectory in 2030.”12World Economic Forum, 2019, The Net-Zero Challenge: Global Climate Action at a Crossroads (Part 1). Meanwhile, commitments in the corporate realm are equally disappointing. A study of the 7,000 companies reporting to the CDP in 2019 found that only a quarter had established an emissions reduction target, and that “[o]n average, both short-term and long-term targets are about half of what would be needed for a 1.5°C world.13World Economic Forum, 2019, The Net-Zero Challenge: Global Climate Action at a Crossroads (Part 1).

As demonstrated by these findings, the problem is not only with the quantity of net zero targets, but also their quality. Almost all current targets across the spectrum of actors center on only Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions. This is problematic because for some actors – especially companies – Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions don’t even make up the majority of their total emissions. In the case of cities, ignored Scope 3 emissions encompass activities such as aviation and shipping – both extremely high-emitting activities.14C40 Cities, April 2019. Defining Carbon Neutrality for Cities & Managing Residual Emissions – Cities’ Perspective & Guidance. Of course, Scope 3 emissions in these sectors are also extremely difficult to abate, and in many ways, in the hands of companies and national or regional governments more than cities. This uncertainty over where responsibility for emissions reductions should fall is relevant for even Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, exemplifying the need for clear, thorough, and adaptable plans to accompany net zero targets.

5. …But there’s still hope, and still much to learn about what makes for effective net zero targets.

Clearly, as with most things related to climate action, the realm of net zero targets is hardly black and white. It’s true that the scale of current net zero targets may be insufficient for limiting warming to 1.5°C of warming. However, it’s also true that net zero targets are much more than the actual emissions reductions they imply. They can encourage other actors to make similar commitments, send political signals that help shift markets, and trigger changes in governmental, technological, and financial structures that will open up possibilities further down the road. We should be wary of dismissing or underestimating existing net zero targets just because they aren’t perfect.

This is not to say there is no work to be done. Before we can gauge the need for revisions to existing net zero targets, however, more research is needed on what effective net zero targets even look like. Because the vast majority of net zero targets have only emerged in the past five years, and the earliest community-wide target years are 2025, little research has been done on commitment follow through. Braving this frontier, the Data-Driven Lab – working with the NewClimate Institute, Oxford University, and CDP – will be publishing an analysis of existing net zero targets from non-state actors in the fall of 2020. It aims to investigate who is setting net zero targets, how these actors plan on reaching their goals, and what qualities signal that a target is robust and likely to be met. Rather intuitively one might hypothesize that actors which provide detailed timelines and set interim targets are more likely to achieve their net zero targets; however, other determining factors are almost certainly at play.

The future of net zero targets is far from settled. However, the information we currently possess suggests a dire need to continue ramping up engagement in the near future; we cannot afford to passively anticipate the development of game-changing technology several decades down the line. Net zero is the buzzword of today, but it’s essential that – more than a buzzword – it becomes a reality. In order for this to happen, actors across the spectrum need to step up their game and make the phrase mean something.

Bibliography:

“Business Ambition for 1.5°C: UN Global Compact.” UN Global Compact: Uniting Business for a Better World, UN Global Compact, unglobalcompact.org/take-action/events/climate-action-summit-2019/business-ambition.

Colenbrander, Sarah & Lazer, Leah & Haddaoui, Catlyne & Godfrey, Nick. (2019). Climate Emergency, Urban Opportunity: How national governments can secure economic prosperity and avert climate catastrophe by transforming cities.

C40 Cities, April 2019. Defining Carbon Neutrality for Cities & Managing Residual Emissions – Cities’ Perspective & Guidance.

“Global Climate Action NAZCA.” United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, climateaction.unfccc.int/views/cooperative-initiative-details.html?id=94.

Global Protocol for Community-Scale Greenhouse Gas Emission Inventories: An Accounting and Reporting Standard for Cities, World Resources Institute, 2014, ghgprotocol.org/greenhouse-gas-protocol-accounting-reporting-standard-cities.

IPCC, 2018: Summary for Policymakers. In: Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, H. O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J. B. R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M. I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, T. Waterfield (eds.)].

Rogelj, D. Shindell, K. Jiang, S. Fifita, P. Forster, V. Ginzburg, C. Handa, H. Kheshgi, S. Kobayashi, E. Kriegler, L. Mundaca, R. Séférian, M. V. Vilariño, 2018, Mitigation pathways compatible with 1.5°C in the context of sustainable development. In: Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty [V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, H. O. Pörtner, D. Roberts, J. Skea, P.R. Shukla, A. Pirani, W. Moufouma-Okia, C. Péan, R. Pidcock, S. Connors, J. B. R. Matthews, Y. Chen, X. Zhou, M. I. Gomis, E. Lonnoy, T. Maycock, M. Tignor, T. Waterfield (eds.)].

UNEP (2019). Emissions Gap Report 2019. Executive summary. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi.

World Economic Forum, 2019, The Net-Zero Challenge: Global Climate Action at a Crossroads (Part 1).

Recent Comments