Image of residents near one of Guangzhou’s waterways, by Andy Leung from Pixabay.

Data has the potential to transform China’s environmental management. While its environmental data still sparks scrutiny, the country is in the midst of a turn towards more comprehensive monitoring, in the service of increasingly ambitious environmental goals. The government has grown its monitoring system to include nearly 2,000 surface water quality monitoring points, and more than 1,400 air monitoring stations across over 330 cities. It has also started experimenting with new forms of data collection, from satellites tracking air pollution to the cloud-based management of vulnerable ecosystems.

The rapid growth of internet access, social media platforms, and mobile apps, in particular, has created new avenues for collecting – and leveraging – environmental data. Two new papers by Data-Driven Lab researchers, in the Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning and the Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, explore the uptake of one of these new tools, the Black and Smelly Waters App, which enables users to flag polluted waterways for review by local government agencies.

Local data, national targets

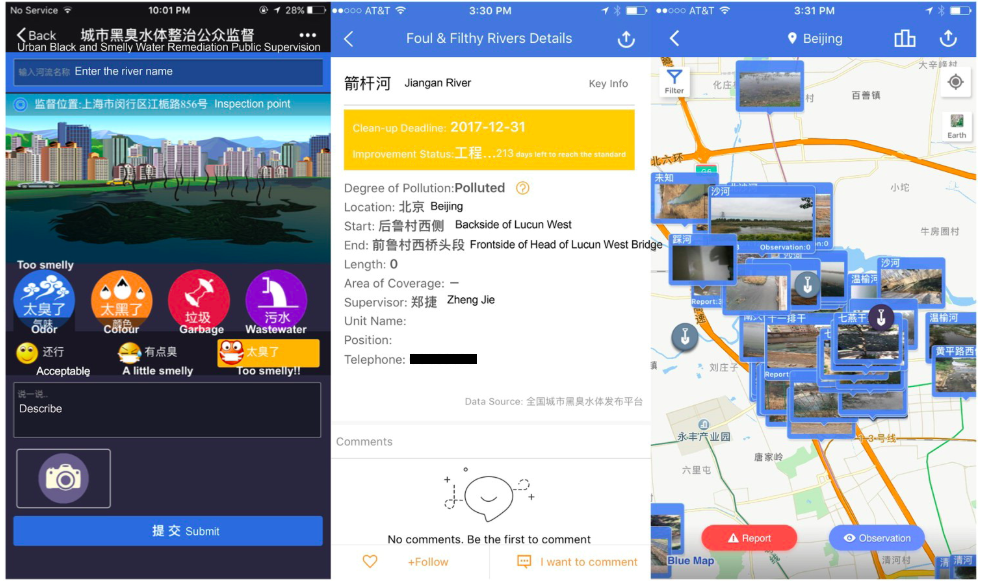

Participants access the app through WeChat, a popular messaging application with close to a billion users, or through the Institute for Public Affairs’ BlueMap app, which gathers and synthesizes environmental data. The app invites users to share a picture of any waterway that they think is “black and smelly,” noting potential sources of sewage and pollution, and ranking the amount of floating trash, water color, and smell. A local government agency follows up within seven working days. The platform tracks the agency’s responses and the progress of any efforts to remediate the site.

Screenshot of the Black and Smelly App on the WeChat platform. The app requires users to use geolocation services on their smartphone to identify a black and smelly water body within 10 meters of their location, add a picture and description, identify any potential nearby sources of sewage or pollution, and rank the water body’s smell, water color, and the presence of trash within it. Users are then provided with a response and follow-up comments from the local agency responsible for the waterway.

As their name suggests,”black and smelly” water bodies have an unpleasant color and odor, typically resulting from high levels of organic pollutants, often contributed by untreated sewage, industrial runoff, or household wastewater. The China State Council’s Action Plan for Preventing and Treatment of Water Pollution (2015–2020) aims to reduce the number of Black and Smelly water bodies to less than 10 percent of urban waters by 2020, and to completely remediate any remaining impaired urban waters by 2030. China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP) and Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development (MOHURD) launched the Black and Smelly Waters app in 2016, to help reach these targets.

The app marks a new twist in the use of citizen science. The app leverages citizen insights to help the central government hold local government agencies accountable to these water quality targets. China’s environmental policy often faces an “implementation gap,” in which the central government sets targets (e.g. for water pollution reduction) and local governments exercise their own discretion in implementing them. The Black and Smelly Waters app represents a unique merger of national priorities and grassroots monitoring to help ensure the local implementation of water management policies.

The papers from the Data-Driven Lab team explore the early impact of this program – and the new mode of governing it represents. Although the initiative is still in its early phases, its reported data offers a window into the app’s uptake; the information participants are recording; and the ways in which local government agencies are responding to this information.

Filling data gaps — in some cities

Citizens have used the app to identify more than twice the number of officially designated black and smelly sites. This result suggests that the program is meeting one of its key goals – to identify additional sites of urban water pollution. Most citizen reports classify waters as polluted, rather than as neutral or acceptable, and choose the lowest-performing classifications when ranking these sites. Water bodies are “too smelly,” “too dark,” and contain “too much trash.”

One paper zooms into the southeastern city of Guangzhou, combining citizens’ black and smelly reports with the city’s water quality data. This comparison revealed that water bodies receiving Black and Smelly complaints have poorer-than-usual water quality. In other words, the app’s users seem to be accurately identifying polluted water, and honing in on the most impaired sites.

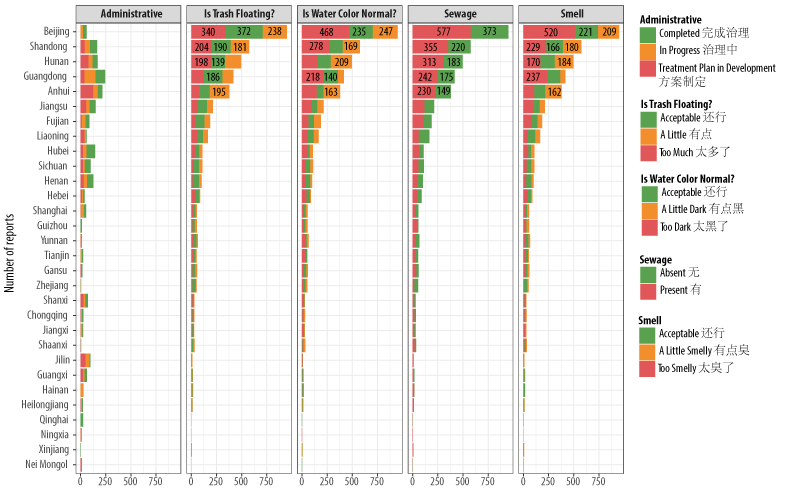

The app’s uptake, however, varies widely across different regions. Most reports (22 percent) were made in Beijing, followed by the neighboring Shandong province (13 percent), Hunan province (12 percent), and Guangdong province (10 percent) – all fairly developed, industrialized regions. Less developed provinces with smaller urban populations, such as Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, Qinghai, and Ningxia, have very few reports. This scattered coverage could limit the app’s ability to fill in data gaps across the country.

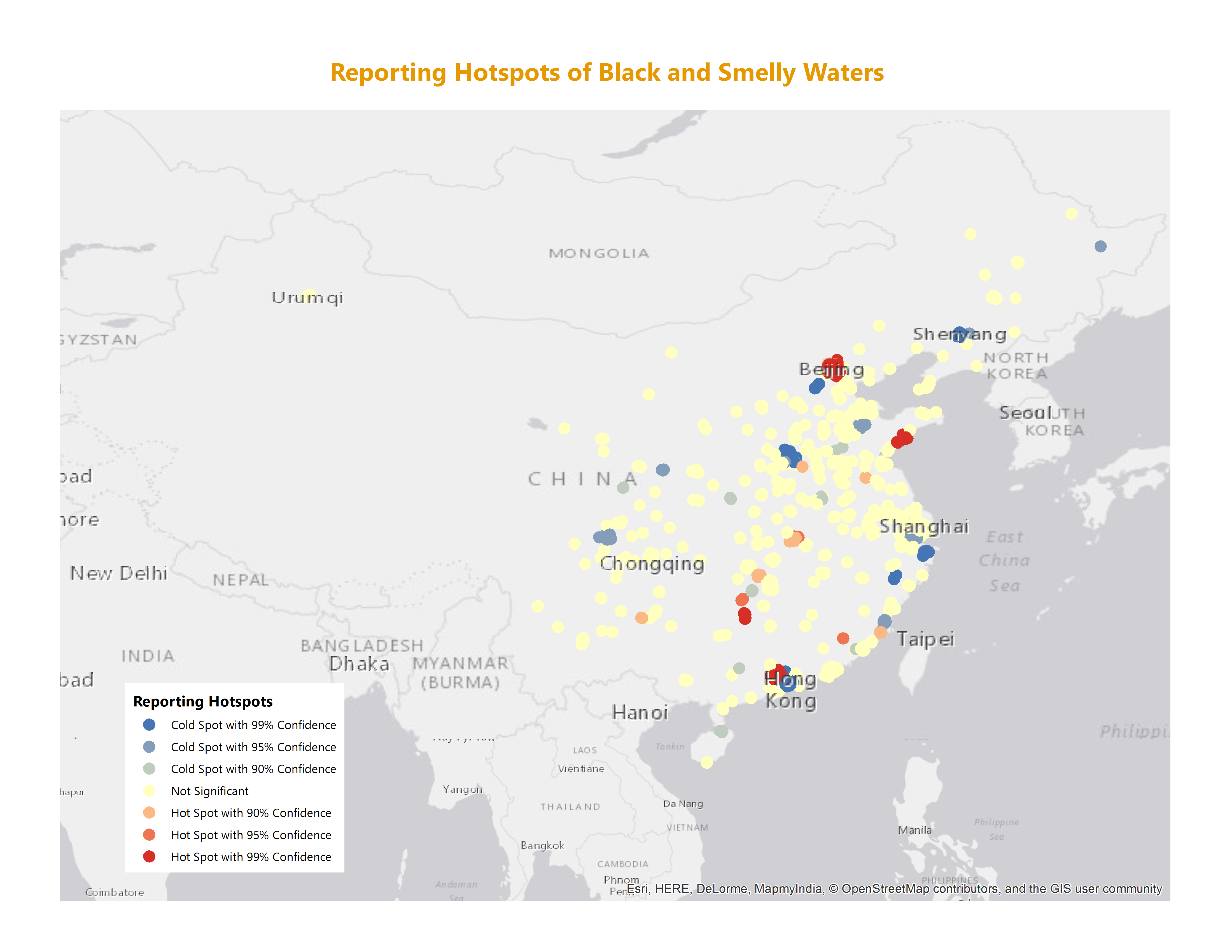

‘Hot’ and ‘Cold’ spots of reported pollution severity through the Urban Black and Smelly Waters app from February 2016 to May 2017. Hot spots refer to clusters of high reported pollution severity (e.g. too much trash, too dark water color, too smelly, and sewage present), whereas cold spots are identified as low pollution levels. Data source: http://gz.hcstzz.com.

The uneven use of the app could reflect a number of factors. Awareness of the program may be highest around Beijing, where environmental NGOs often cluster. Socioeconomic factors can constrain ownership of smartphones and access to the Internet, which could limit participation. Additionally, some research has suggested that different degrees of industrialization could account for variations in environmental concern across different regions. More research is needed to know for sure – but finding ways to fill data gaps across the country will be vital to preventing pollution from simply shifting to less closely monitored areas.

Does information lead to action?

Our analysis also shows that government agencies are remediating black and smelly sites flagged by citizens, although complaints still far outnumbered reports of treatment progress at the time of the analysis. About a third of black and smelly reports were listed as “completed” (e.g. completely remediated), while the majority (around 60 percent) were still being addressed. As with reporting, the remediation of black and smelly sites varies regionally, with hot spots of progress clustered around urban areas like Beijing, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Chongqing. The low rate of treatment could reflect the fact that this data was drawn from an early phase of the program – many remediation efforts could require additional time, still be underway, or not yet be reported.

The number of complaints registered by province in China varies, with the most number of reports registered in Beijing and its neighboring province Shandong. Most complaints registered are negative – the water color is generally too dark, floating trash is ‘too much,’ and the smell is ‘too smelly.’ In terms of administrative data, the number of reports that are being addressed are fewer in number with the most in Guangdong and Anhui provinces. Data source: http://gz.hcstzz.com.

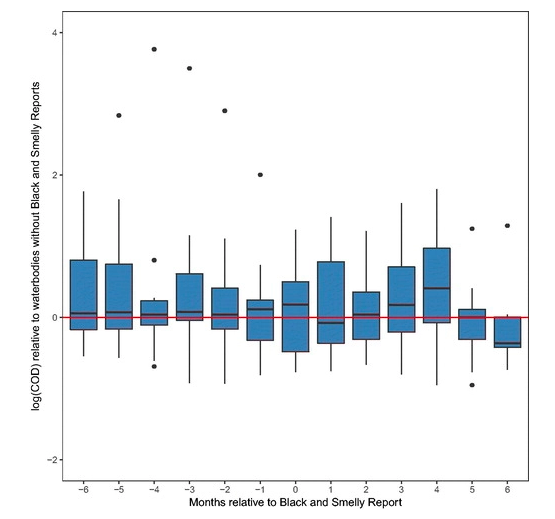

To better understand the app’s impact on water quality, we again looked more closely at the city of Guangzhou, the capital of Guangdong province in southeastern China, comparing information with the app from monthly water quality data. Using a fixed effects regression model, we explored whether citizens’ black and smelly water reports affected a suite of water quality indicators in the city’s waterways: the water’s transparency; its levels of dissolved oxygen, ammonia nitrogen, and phosphorus; its chemical oxygen demand; and its classification on China’s water quality index. The model revealed that chemical oxygen demand improved, decreasing by 36.3 percent and 38.9 percent, five and six months after citizen reports were made. It did not detect any significant changes in the other water quality indicators.

Log-transformed COD levels in Guangzhou water bodies with Black and Smelly Water reports relative to those bodies without reports 6 months before and after reports were made (n = 576).

This improvement in chemical oxygen demand provides preliminary evidence that the Black and Smelly Waters app may be reducing water pollution levels in this city. But the fact that only one water quality indicator improved invites more questions. The change in chemical oxygen demand might reflect a reduction in industrial wastewater pollutants, such as heavy metals, without a corresponding reduction in more organic, biodegradable forms of pollution, which affect all of the water quality indicators. Additional data would be needed to verify this hypothesis – and to more thoroughly test the impact of the app across other cities. At the moment, however, few municipalities publicly share detailed water quality data.

A new monitoring model?

Finding ways to meaningfully track progress – of black and smelly sites’ treatment, and of the program’s impact on water quality goals – could be vital to the program’s long-term success. Citizen’s long-term use of the app may depend on their confidence that it will spur meaningful remediation. An expanded “river chief” system – which has appointed approximately 1.1 million guardians for specific waterways – echoes the app’s goals of enhancing accountability and creating a clear line of communication for reporting and tracking impaired waters. But anecdotes suggest its effectiveness depends on the capacity for these officials to act on citizen’s reports.

There may also be limits to the ways local agencies can address the underlying causes of water pollution. Systemic issues – like the need to connect households to a wastewater treatment system – can be difficult to tackle quickly. Upstream sources of pollution may fall outside local agencies’ jurisdiction.

Despite these challenges, the results suggest that this combination of emergent technology and civic engagement can overcome some of the challenges of reaching national pollution reduction goals. As China continues to expand its monitoring system, this approach could hold lessons and ideas for overcoming data and implementation gaps across a wide suite of environmental issues.

Recent Comments