Hanoi – a city typically known for its charming Old Quarter and mouth-watering pho – has recently attracted attention for a different reason: poor air quality. On September 29, the U.S. Embassy’s monitoring station in Hanoi registered hourly Air Quality Index (AQI) levels of “very unhealthy” pollution, described as “health warnings of emergency conditions.” The Vietnamese government issued an official air pollution advisory urging citizens to protect themselves and limit outdoor activities. And in early November, just this past week, AQI levels registered at monitoring stations as “hazardous” and “very unhealthy.”

Clarity surrounding the drivers of pollution in Vietnam is important for improving the air. Officials cited low rain and agricultural burning as the reasons for Hanoi’s poor air in September, and attributed more recent pollution to a temperature inversion, which traps polluted air at lower altitudes. While short-term factors like these play a role, it is crucial that pollution control also consider long-term causes such as industrial emissions, motor vehicles and coal combustion. For instance, coal generation in Vietnam is set to increase five-fold, to 55 gigawatts by 2030, posing an imminent threat to achieving consistent clean air.

One silver lining to the smog is that Vietnamese non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are getting more creative in their tactics to address the country’s environmental woes. In August, I traveled to Hanoi, Vietnam to support Data Driven EnviroPolicy Lab’s (Data-Driven Lab) efforts to explore the impacts of China’s Belt and Road Initiative on land use change and urban development in Southeast Asia. While there, I separately met with a handful of Vietnamese NGOs that are adopting data-based approaches to improve environmental quality and governance. Two organizations leading the charge are the Green Innovation and Development Center (GreenID) and the Centre of Live and Learn for Environment and Community (Live & Learn). Both of these NGOs have made strides in harnessing the power of data to expand public awareness and civic action on air quality.

GreenID and Live & Learn are part of a growing movement of “third-wave” data that adopts innovative strategies to improve information availability and leverage data for policymaking. Examples of third-wave approaches include citizen science, crowdsourcing, big data, public engagement in environmental management, and social media. Third-wave data can help inform decision-makers at a speed and scale that doesn’t rely solely on traditional institutions, which can be slow and bureaucratic. In Vietnam, where official data is often scant or incomplete, third-wave data could help prevent “pollute first, clean up later” mindsets from leading to irreparable environmental harm.

GreenID analyzes data to strengthen air quality policies

GreenID was founded in December 2011 to further sustainable development in Vietnam “by promoting the transition to a sustainable energy system, good environmental governance and inclusive decision processes.” Its executive director, Ms. Nguy Thi Khanh, was the first Vietnamese citizen to win the Goldman Prize when she was awarded the world’s “environmental Nobel Prize” in 2019. Among GreenID’s transformative work is its role since 2016 as the first Vietnamese organization to publish “air quality reports” analyzing the causes, impacts and solutions of air pollution in Vietnam.

GreenID’s 2018 Air Quality Report illustrates how NGOs can get creative in applying third-wave data approaches, despite challenges with data availability and coverage. GreenID analyzes data from monitoring stations at the U.S. Embassy in Hanoi and U.S. Consulate in Ho Chi Minh City. It supplements this data with figures from ten additional outdoor air quality sensors set up by Puritrak, an environmental monitoring company. Data from ten stations operated by the Hanoi People’s Committee and analysis results from the Northern Center for Environmental Monitoring are also examined, but data for the rest of Vietnam apart from Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City is still insufficient for analysis.

According to GreenID, “We always try to utilize all publicly available resources to give the best available picture as much as we can. Although the collected data is not yet able to provide full indications of air quality in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City and more measuring stations need to be established and hourly historical data need to be provided and used more openly, this report can give warnings of air quality in Vietnam’s two important cities.”

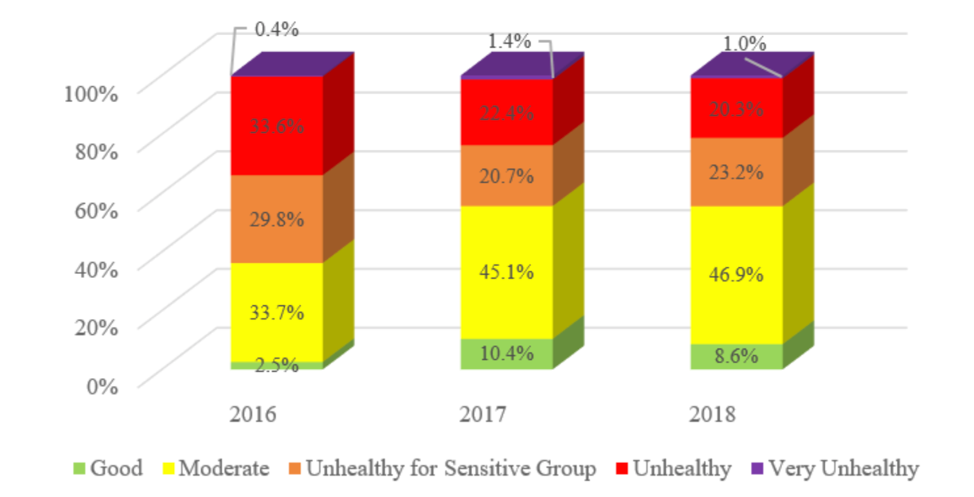

Comparisons of hourly monitoring station data from the US Embassy over 2016-2018 show that air quality improved from 2016-2017, with “Good” and “Moderate” levels rising close to 10%. No significant changes were seen over the next two years, despite a slight fall in PM2.5 levels. Source: GreenID’s 2018 Air Quality Report.

The reports analyze the extent to which air quality accords with standards such as Vietnam’s National Technical Regulation on Ambient Air Quality and the World Health Organization’s Air Quality Guidelines, and apply modelling techniques to evaluate potential source locations of the pollution. Results are then used to inform policy recommendations aimed at key government stakeholders, as well as scientific and technical actors, NGOs, media and the general public.

Recent Vietnamese government action on air quality provides some reason for optimism. Officials launched an air quality action plan in 2016 that provides targets through 2020 and guidance through 2025. On the monitoring front, Hanoi plans to add 20 fixed automatic air monitoring stations by 2020 and 30 more by 2030, in conjunction with the French organization AIRPARIF. Vietnam still lacks a federal law on air pollution, but with organizations like GreenID working to effectively translate that data into policy recommendations, improved data availability could bolster calls to adopt a Clean Air Act.

Live & Learn expands public awareness of air quality impacts

Live & Learn, which was founded in 2009, focuses on education, mobilizing communities, and facilitating supportive partnerships to “foster a greater understanding of sustainability, and to help move towards a sustainable future.” The organization is a central cog in the “Clean Air, Green Cities” project funded by USAID, which connects actors in air quality management and includes partnerships aimed at increasing data availability and accessibility. One part of the Clean Air, Green Cities project is a partnership called PAM Air to install air quality monitoring devices and provide greater public access to air quality information.

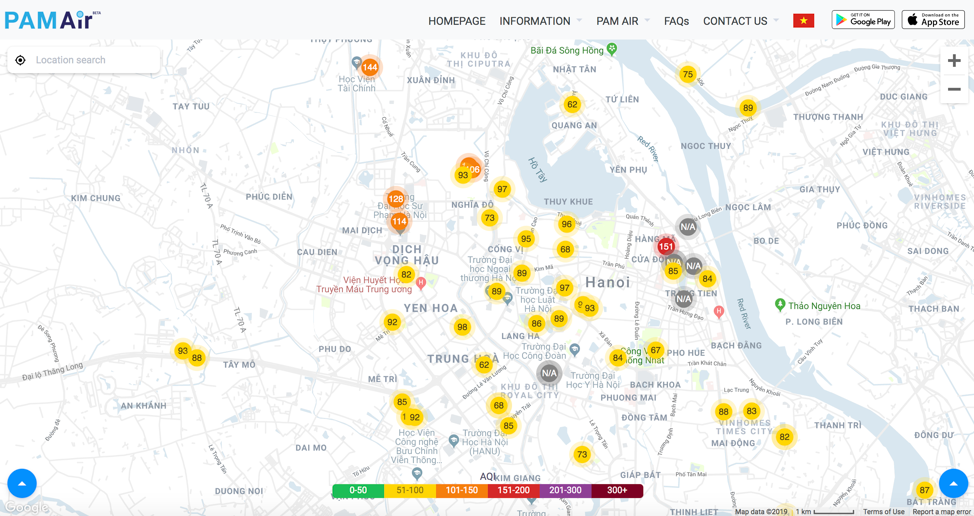

PAM Air’s data is meant primarily to improve public air quality understanding, rather than for detailed scientific research. According to an open letter on its website, “PAM Air was created with the desire to contribute to the community a useful but simple and easy-to-use tool (application) so that any individual can follow and update information on air quality.” PAM Air’s website describes one of the program’s aims as “supplementing the government’s existing air monitoring system (there are few public monitoring stations in big cities and they are not real-time).”

Screenshot of PAMAir’s website, taken at 11 a.m. local time on Wednesday, October 31, 2019. Air Quality Index values range from “Moderate” to one station showing 151, a value categorized as “Unhealthy.”

PAM Air’s system consists of three components: outdoor air monitoring devices that transmit data using 3G networks and Wi-Fi; a website that consolidates data from these monitoring devices in map form, and provides real-time ambient air quality data, 24-hour air quality trends, as well as information on health impacts; and a mobile application that personalizes this data based on the user’s location. All of the data is stored and managed by PAM Air’s back-end platform. Apart from the stations installed and operated by PAM Air, the website – which opens to an air quality map of Hanoi, but zooms out to reveal data from a variety of locations throughout Vietnam – also integrates data from other sources, such as the U.S. Embassy.

Live & Learn uses data as the basis to raise air quality awareness for schools and communities, provide information to vulnerable groups, and support basic research efforts in locations with little or no available information. As of April 2019, the organization’s “citizen science program” had engaged four schools and installed 70 AirSense monitoring devices to use in educational activities that teach school children how to track and interpret air quality. Its “AQI flags” program provides schools with colored pennants to indicate current air quality with an eye for protecting the health of schoolchildren. Moreover, an October 2019 workshop helped media correctly understand technical aspects of air pollution so that they could more accurately report on the issue. These efforts will all benefit different segments of the public to be able to track and interpret air quality, and build public support for the expansion of data availability.

What’s next for third-wave approaches in Vietnam?

Third-wave environmental data holds massive potential to fill current information gaps in Vietnam at speed and at scale. Still, these approaches also face their own challenges. In early October 2019, the global air quality app AirVisual was temporarily made unavailable for download in Vietnam following a coordinated social media attack. The online outcry erupted when an online chemistry teacher accused AirVisual of manipulating its data to sell more air purifiers after Hanoi topped a live pollution ranking of around 90 cities worldwide.

A statement published by AirVisual asserted, “Efforts to suppress open and free air pollution data, rather than address the emission sources that have created the problem, are misguided and have negative health and environmental implications.” On one hand, lack of sufficient data from different sources for comparison can lead to misunderstandings. Furthermore, third-wave data in itself does not guarantee that the government will act on it or share it.

Greater availability of official data could buttress third-wave approaches. The 2014 revisions to Vietnam’s Law on Environmental Protection include an entire chapter (Chapter XIII) on Environmental Information, Directive, Statistics and Reporting, requiring government bodies to publish information in a manner convenient to recipients. On a practical level, Vietnam’s national-level Center for Environmental Monitoring has taken steps to improve environmental information transparency. However, in a country where only 19 provinces have automatic air quality monitoring stations, there is still a long way to go to satisfy the public’s environmental right-to-know.

Data is a powerful tool to enable citizens to protect their health and support environmental protection efforts. GreenID and Live & Learn are taking crucial first steps to harness data to improve air pollution awareness and access to information. While air quality is only the tip of the iceberg of environmental challenges, the growing momentum of third-wave data holds massive potential to accelerate top-down and bottom-up efforts to improve information availability in Vietnam.

Special thanks to Ms. Nguyet Do Van of the Centre of Live and Learn for Environment and Community, and Ms. Nguyen Thi Anh Thu and Ms. Tran Vu Diem Hang of Green Innovation and Development Center.

Recent Comments